Like an elegant ante-pasta platter, Dropped Names kept me eating one bite-sized chapter after another, some sweet, some salty, more bittersweet. These are anecdotes that actor Frank Langella has perfected in decades of late-night after-drinks conversation with other actors. In committing these stories to print, Langella has also reflected on the craft of acting, and the dangers of celebrity.

[Photo: Langella as "Dracula," in a film adaptation in 1979 of his star turn on Broadway; today; and as "Nixon," a role created for the play Frost/Nixon and re-created for the film. See my reflection on Frost / Nixon.]

For sweet, we have from Marilyn Monroe a kind word, just one, that fires ambition in the geeky sixteen-year-old Langella. There's John F. Kennedy, in yellow trousers, putting young Langella at ease. Gray and gay Noel Coward flirts with Langella, but the younger man feels only admiration and gratitude for Coward's rapt attention; at a tribute years later, Langella sees Coward's eyes well with tears. Actresses past their prime maintained their dignity and air of mystery: Delores Del Rio, Billie Burke, Loretta Young. Langella calls Raul Julia "my boyfriend" who comes across as an overgrown puppy of a man, exuberant and without guile.

For bittersweet, we have greats or near-greats in decline. Some are just tired: James Mason, James Coburn, Jack Palance. A mediocre director named Cameron Mitchell, once a handsome actor, now squeezed into a suit coat that fit him in his glory days, blushes as he jigs for the cast and crew. The great actor George C. Scott, directing Langella in Coward's Design for Living, leaves rehearsal after draining a six-pack and a bottle of Scotch; gets pissed off (and on) during a drunken confrontation with Langella at a urinal (giving Langella the opportunity to make the pun "I rained on his tirade"); and wanders off stage during a sold-out performance of Inherit the Wind, muttering "I'm sorry... forgive me."

For salacious, we have Langella's affairs, and a slew of self-centered megolomaniacs. Of the former group, I'll say nothing; this is a family blog. Of the latter group, famed "Method" teacher Lee Strasberg leads the pack: Not only does Langella detest the pompous little man, but he quotes friend Stella Adler saying, "It will take one hundred years to undo the harm he has done to the acting community" (29). Anthony Quinn sends a personal assistant to tell Langella that "Hi" is not a sufficiently respectful way to address Mr. Quinn. Richard Burton is a drunken bore who monotonizes conversation in Langella's dressing room for hours; Yul Brynner's "King" persona carries over into everything he does.

About his own profession, Langella straddles two poles. Strasberg was, in Langella's understanding, about indulging one's own emotions; while England's quintessential classical actor John Gielgud (my drama teacher's drama teacher) was too far removed from emotional truth, though he did seek roles outside his comfort zone. Langella frequently castigates actors, also playwright Arthur Miller, for lacking any introspection. There's got to be technique; the emotion can't be some kind of personal therapy; and, as Maureen Stapleton said to Langella, "Ya' gotta mean it, baby" (266).

There's an odd undercurrent here about masculinity. Langella gives us Robert Mitchum and James Coburn as their agents would have him do, as strong, silent, hard drinking, unsentimental he-men. Langella laughs at his own adolescent behavior when he competes with novelist William Styron over an inch or two in the boudoir of a French mistress they shared. But it's man's man George C. Scott who surprises us most. Asked in flight, drunk, what he would have done instead of acting, Scott told Langella, "I would spend the rest of my life sitting at the bedside of the real men in veterans' hospitals playing chess... But why would they want to be bothered by some faggot actor" (188)?

Near the end, Langella passes on universally good advice from heiress Bunny Mellon. Asked how to talk to famous people, she said to just repeat the last few words of everything they say, as a question. Brilliant!

Monday, August 24, 2015

Saturday, August 08, 2015

Conversation Radio at WABE-FM, Atlanta

Until I plugged in my ear buds and started riding my bike this summer, I was among those mourning the loss of classical music programming at WABE, Atlanta's premiere public radio station. But I gave a try to the talk shows City Lights and A Closer Look.

Until I plugged in my ear buds and started riding my bike this summer, I was among those mourning the loss of classical music programming at WABE, Atlanta's premiere public radio station. But I gave a try to the talk shows City Lights and A Closer Look.Nine weeks and nearly 2000 miles later, on the stormy evening before I return to school for faculty work days, I know I'll remember this summer for conversation, the way I remember other summers for "Sweet Caroline" or "Call Me Maybe."

[Photos, WABE.org: Lois Reitzes; Denis O'Hayer and Rose Scott]

"A Closer Look," hosted by Denis O'Hayer and Rose Scott, focuses more on Atlanta's metropolitan area, economic trends, policy choices, and controversies. Mayor Kasim Reed paused to comment on how they were giving him a hard time, and another official later thanked them for not letting Reed off easy. No matter what, Denis and Rose, no less than Lois, presume that their interlocutors are decent, intelligent, and well-prepared to answer critical questions.

So, pedaling through a tunnel of greenery, dodging squirrels and the occasional rabbit, I was always thinking. For awhile, I tried to keep a list of striking bits until the quantity overwhelmed me. Here are a few:

- Chuck Palahniuk's violent Fight Club belies a soft-spoken, thoughtful, earnest writer who admires my guy, John Updike. "Everyone listening should read or re-read Updike's story about the A&P." His own short story about a boy parroting grown-ups' offensive jokes suggested a lot about us. Palahniuk worries about an insidious feedback loop between MFA teachers, their graduates, and the next generation of MFA teachers.

- Cellist Lynn Harrell learned from his father, the singer, to let the cello "breathe"

- Is 6000 pages too long for a memoir? A panel of thoughtful critics and writers didn't settle for the one obvious answer considering My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgaard. Maybe we do have too much fiction in our lives, dozens of stories flashing at us in image and sound every hour. The author admitted, "The first ten pages are the best; the rest isn't up to my usual standards." Why did the panelists wait an hour to mention that the title was Hitler's?

- Local musician Scott Stewart kept up a summer-long dialogue with Lois about film music with numerous sound clips. I know to look for more by Giachino; Korngold's noble, melancholy music made me cry; the tribute to Horner brought out variety I hadn't heard before; and even the segment on video games illustrated the orchestrator's craft. I want to remember Korngold's response when Max Steiner said, "During your ten years in Hollywood, my music has been getting better and better, while yours has been getting worse and worse." Korngold said, "That's because you've been stealing from me, and I've been stealing from you."

- The late Elmore Leonard said, "If it sounds like writing, I re-write it."

- B.B.King was scared in 1967 when a roomful of white hippies gave him a standing ovation before he played a note; his delight and gratitude for that evidently carried over to his dying day four decades later.

- I had my eyes opened to artists I've not appreciated before through tributes to Buddy Guy, Nina Simone, Sarah Vaughan, some by WABE's jazz deejay affectionately known for decades as H. Johnson.

- Louis Armstrong's music, his home, his home-recordings, his dismay at being called an "Uncle Tom" all came across in an audio tour of the home his wife Lil made with him.

- What's most important about a brand of bourbon, says the author of a book on America's beverage, is not in the bottle. The legends that go with the labels began largely as marketing ploys, but are now so old that they're legend enough.

- Conversation with the writer who moved in next to Harper Lee's family home gave us insight before the controversy over Go Set a Watchman. She returned after, for follow-up.

- Zombie maven Max Brooks wrote World War Z on the models of real-life oral histories, to emphasize how heroes don't win a war; it's a community effort. His zombies are slow and stupid (not like the super-powered ones in the movie, which he disowns) because we are to blame for repeated plagues and scourges, through denial, inertia, gullibility. Brooks gives the example of AIDS-HIV, but I can think of others. Even Hitler gave ten years' warning. Brooks' latest work about vampires during a zombie apocalypse is his version of what he sees on college campuses today: children of privilege who've never been allowed to experience failure.

So, with school looming, I know this summer is over. I'll miss my long dog walks with Mia, old Luis, and my friend Susan; I'll miss the bike rides and feeling fit as I fill up with school lunches and sit reading papers. And I'll miss "City Lights" and "A Closer Look." They were the soundtrack of my summer!

Wednesday, August 05, 2015

We are Jesus, Not God

"So who made you God?"

I want to ask this when people of my own comfortable socio-economic status argue that this or that liberal policy will just increase dependence on the state among the lower classes. A bright guy like Paul Ryan tries to soften his rhetoric about "makers and takers," but it's still just Social Darwinism: let the weak (lazy, addicted, promiscuous) ones go homeless, go to jail, return to their home countries, whatever, and let the "fittest" keep all their stuff, unburdened by taxes and unbothered by public projects anywhere near their backyards.

One religious friend of mine opined that we should never have extended the vote to the unpropertied masses, as they just elect politicians who promise the most benefits. I notice that social Darwinism is bedrock belief among my acquaintances who dislike the real Darwinism.

But Jesus pointedly doesn't discriminate among the people he helps. Disciples ask him, "Who sinned, the blind man or his parents?" Jesus doesn't care. Does the victim belong to a despised category (Samaritans, Gentiles, lepers, women, "the unclean")? Regardless, Jesus touches, heals, nourishes.

Jesus commands us to follow his example. Jesus says, straight out, that the kingdom of heaven is reserved for those who came to his aid when he was hungry, thirsty, a "stranger" (meaning, an immigrant), naked, sick and in prison. Asked by disciples when he was ever in such dire straits, he replies, "As you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me" (Mt 25.45). No drug tests, photo ids, or means testing required.

Jesus also empowers us to follow his example, so long as we do so in community. Any "two or three" gathered in his name -- that is, representing Jesus -- have power: "Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven; whatever you loose on earth is loosed in heaven," he says to his disciples. (Mt 18:18. The same story also is applied to Peter alone in 16.19).

When I've heard politicians and preachers decry how the Supreme Court has threatened "core religious beliefs," I have to wonder what "core" means to them. Teachings about justice for the poor and caring for the weak is core to both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. But Jesus is most angry whenever someone presumes to judge another for any breach of ancient purity laws.

I know that free markets encourage innovation, and I know that state-directed economies are stultifying and coercive. In between, there's a vast range of choices. (See my blogpost on economist Wilhelm Ropke.) If we support government policies that redistribute a portion of our wealth to others in need, then we can deal with shirkers in some other separate way. We can do what Jesus would do, and leave judgement to God.

I want to ask this when people of my own comfortable socio-economic status argue that this or that liberal policy will just increase dependence on the state among the lower classes. A bright guy like Paul Ryan tries to soften his rhetoric about "makers and takers," but it's still just Social Darwinism: let the weak (lazy, addicted, promiscuous) ones go homeless, go to jail, return to their home countries, whatever, and let the "fittest" keep all their stuff, unburdened by taxes and unbothered by public projects anywhere near their backyards.

| [Cartoon posted by Ben Witherington.] |

But Jesus pointedly doesn't discriminate among the people he helps. Disciples ask him, "Who sinned, the blind man or his parents?" Jesus doesn't care. Does the victim belong to a despised category (Samaritans, Gentiles, lepers, women, "the unclean")? Regardless, Jesus touches, heals, nourishes.

Jesus commands us to follow his example. Jesus says, straight out, that the kingdom of heaven is reserved for those who came to his aid when he was hungry, thirsty, a "stranger" (meaning, an immigrant), naked, sick and in prison. Asked by disciples when he was ever in such dire straits, he replies, "As you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me" (Mt 25.45). No drug tests, photo ids, or means testing required.

Jesus also empowers us to follow his example, so long as we do so in community. Any "two or three" gathered in his name -- that is, representing Jesus -- have power: "Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven; whatever you loose on earth is loosed in heaven," he says to his disciples. (Mt 18:18. The same story also is applied to Peter alone in 16.19).

When I've heard politicians and preachers decry how the Supreme Court has threatened "core religious beliefs," I have to wonder what "core" means to them. Teachings about justice for the poor and caring for the weak is core to both the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. But Jesus is most angry whenever someone presumes to judge another for any breach of ancient purity laws.

I know that free markets encourage innovation, and I know that state-directed economies are stultifying and coercive. In between, there's a vast range of choices. (See my blogpost on economist Wilhelm Ropke.) If we support government policies that redistribute a portion of our wealth to others in need, then we can deal with shirkers in some other separate way. We can do what Jesus would do, and leave judgement to God.

Tuesday, August 04, 2015

Ann Cleeves' Thin Air has

Thick Atmosphere

In Thin Air, novelist Ann Cleeves plays one tight-knit community

In Thin Air, novelist Ann Cleeves plays one tight-knit community against the other. There are young urban professionals gone up to the northernmost British isle for a wedding, and the team of detectives who descend on the community when the bride vanishes.

The island itself, hours from the mainland, in the eerie twilight of a sun that never sets, naturally bears a small, insular community. It has a scandal of its own: the neglected girl who drowned generations ago and now haunts the foggy cliffs and permeates the story.

The crime sharpens conflict among the communities, and also within them.

For those of us who have followed the series from the start, it's good news that brooding detective Jimmy Perez is a little less brooding, here, and a little more sensitive to his boss from the central office, named "Willow" by her aged hippie parents. Even better, we see more growth and even a hint of romance for sidekick Sandy.

In each of Cleeves's novels that I've read, when the story reaches a breathlessly exciting conclusion, we face two or three chapters of stagey question-and-answer sessions explaining what really happened. If there's some way to mete out revelations earlier, so that only one or two final questions remain at the denouement, I wish Cleeves would find it.

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Sondheim Anthologies:

"You have to think the whole time!"

Thinking of putting on a show of Sondheim songs? You're going to face people like my parents'

friends. They walked out on a fine production of Side by Side by Sondheim back in 1980. "It was terrible," they said. "You had to think the whole time!"

I'm thinking about this now because I recently saw the Atlanta premiere of Sondheim on Sondheim

by Act 3 Productions, co-directed by Michelle Davis, Chris Ikner,

musical director Laura Gamble, and choreographer Johnna B. Mitchell. A

portion of the audience whooped and cheered for

all the showstoppers. A man was humming "Sunday" in the line for the

restroom. But the woman behind me kept complaining, "I

can't figure out what's going on. It's just overwhelming." She thought

she'd skip act two because she didn't know any of the songs listed in

the program.

Even

knowing all the songs by heart, I have mixed feelings about this and

the other anthologies. I own recordings of them all and I've seen most

of the ones pictured in my collage above. With this Atlanta production

fresh in my mind, I've got a few do's and don'ts -- mostly don'ts.

Do sing

your songs as if you are in intimate conversation. It's good advice

relayed by an observer to Barbara Cook's "master class," who writes that

a young man had earned big applause for his performance. She sat him

down with her, knee to knee, held his hands, and had him sing the song

directly to her. The singer achieved new credibility and depth.

In Sondheim on Sondheim

last week, some of the performers got that right. Michaele Postell

delivered "In Buddy's Eyes" as if telling her mixed feelings to a

sympathetic friend. "Send in the Clowns," on the other hand, might have

been just another pop ballad, performed straight to the audience with

strong voice and energetic gestures -- but not to the lover who has just

said "I'm sorry, but, it's over."

Don't mash up the songs. Yes, I and the whoopers do appreciate the ingenuity of intertwining two torch songs, but when the arrangers interrupt "Not a Day Goes By" at its climax to begin "Losing My Mind," they allow neither song room to breathe. "A Weekend in the Country" was wonderful, staged during the first Carnegie Hall birthday anthology; here we got so little of it in a medley with "Ever After" that both songs lost their punch. Save the clever arrangements for tributes that attract the cognoscenti. For the lady behind me, and for at least one of my own guests, all the mash-ups were puzzling.

Don't do the songs without context. Sweeney Todd's "Epiphany" was full of sound and fury, but -- you know the rest. The audience was just puzzled. Who's "Mrs. Lovett?" Where are we? What "chair?" "Waiting Around for the Girls Upstairs" chills and thrills someone who knows what's going on, but how were the others to know that we're witnessing "ghosts?" On the other hand, the pair of songs from Assassins were anchored in the world of that show, and got the laughs and chills they should.

That said, I cannot imagine a better provider of context than Sondheim's own interviews. I have to confess that I found myself looking forward to Sondheim's commentary more than to the musical numbers. In SOS, and in the documentary Six by Sondheim, he's an engaging storyteller, giving us elegant thumbnails of each situation along with his thoughts about his intentions writing each song. He got the biggest laughs, and his anecdote about Hammerstein's last gift to him was among the most affecting moments. (Read my review of Six by Sondheim)

Back in 1975, Ned Sherrin's clever patter gave Side by Side by Sondheim its forward movement, as each song exhibited proof of Sherrin's thesis that Sondheim was/is Broadway's most accomplished lyricist and one of its most adventurous composers.

Don't contrive a whole new context for the songs. Same reason: When a man in tux sings "Hello, Little Girl" to a buxom maid in Putting it Together, the Little Red Riding Hood references are creepy- funny at first, but creepy-creepy by the time we get to specific references to crunching her bones. For the same show, Sondheim re-wrote lyrics of "Now" from "A Little Night Music" to introduce a segment based on party games. It was an awesome stunt, but not nearly so exciting as the original "Now."

Craig Lucas's Marry Me A Little breaks

all my rules, creating an artificial new context for all the songs,

often mashing them together. I've never seen the show, but I understand

the two characters never meet, except in mind. Do the young man and

woman face each other when they seem to be singing to a partner? Yet,

judging just from the two recordings, I sense that it's a funny,

sometimes raunchy, often touching anthology. It may help that these

songs are all "lost" songs that never lived in context for most of us.

Do try.

We actors know, Sondheim writes material that brings out the best in

us. If the production gives us the right context, if the staging

doesn't detract, if we don't settle for generalized feelings in songs

that typically move through a spectrum of thoughts and emotions -- then

we may spark new interest in the uninitiated. Sondheim never writes for

people who'd rather not think.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

Atticus Finch and Superman: Who Owns Them?

Judging a book by its coverage, Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee's first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, portrays Atticus Finch in a different way. I hear that the novel concerns grown-up Jean Louise Finch finding herself disillusioned upon a return trip home. Should we now dig under the surface of Mockingbird for the "real" -- racist, mean-spirited -- Atticus Finch?

Nah.

Some characters, icons of the culture, take on a life of their own. They exist in a Platonic sense, as ideals that we all more - or - less share. The creators of a new Superman movie or comic book can explore the character, give a new angle on him, trim him down or buff him up, but cannot touch the essence of him without exciting the same kind of passion I've heard about Watchman. A priest I know got into it with me over Man of Steel because Superman at the end [SPOILER ALERT] kills his nemesis. The priest said, that's not how the real Superman does it.

But, of course, Superman was once just the idea of a couple of Jewish teens in New York, and he was a wise-cracking brute who didn't fly, but "leaped over buildings in a single bound." That character developed through decades of work by new artists and writers in comics, directors and actors in media. At age 11, when Mom and Dad gave me a hardback anthology of Superman comics, I found historical interest in those original stories, but I saw them as a kind of primitive first approach to the character I'd grown to love in the 1960s.

So let it be with the Atticus presented in this newly published work. Let him be a sign of Harper Lee's development. As my friend Susan Rouse pointed out, every twenty-something who goes away to college returns home to find a whiff of something rotten to disdain. Mockingbird is the work of a more mature woman. Let this earlier version of Atticus show us how racial prejudice has long been a part of the fabric of American culture, underlying thoughts and deeds of people who were (are?) otherwise fair-minded. Let us be thankful that Harper Lee, maturing under an editor's mentorship, stripped away the parts that weren't the "real" Atticus.

And let us be confident that generations of trial and error, argument and adulation, prequels and sequels, additions and revisions, will only deepen our appreciation of the real Superman and the real Atticus.

[I developed these ideas in earlier articles: "Superman Returns": Myth or Merchandise? and So, How Did You Like "Man of Steel?" I reflect on To Kill a Mockingbird as the World's Last English Teacher to Read TKM.]

Thursday, July 09, 2015

Chet and Bernie Close to the Bone:

Scents and Sensibility

Riding shotgun in Bernie Little's Porsche convertible to confront some bad guys, our narrator Chet "the Jet" places a reassuring paw on Bernie's knee, causing the car to lurch forward "in a way that never gets old." In spite of his worries, Bernie laughs, and Chet, our canine narrator, considers, "Life couldn't be any better than this. So why not just keep driving and never ever stop? I tried to think of a good reason" (282).

Chet keeps up an internal monologue that never gets old. Chet made me smile on every page, and I often laughed out loud, as when he explains how to open a locked door, "something Bernie and I had been working on. You slide the bolt open with your paw and then get a steak tip: that's all there is to it. Give it a try sometime" (186). After this, the eighth book in the series, why shouldn't Chet and Bernie just keep going and never ever stop?

Still, author Spencer Quinn signals early on that this series may be reaching a climax. For the first time, Bernie's neighbors, the Parsons (and little dog Iggy), are integral to the plot, bringing the story literally close to home. Their sorrow and humiliations feel real, as Bernie investigates their son's ties to kidnapping, drug dealing, murder, and, incidentally, the uprooting of legally protected cacti. A corrupt policeman named Mickles, who calls Bernie his "nemesis," shows up early and often, leading us to expect some kind of final showdown. There are moments of doubt when Bernie wonders aloud if he's suffering early onset dementia, and the signs are there.

Then, there's the emergence of Shooter, a puppy who looks and smells a lot like our narrator. Longtime readers of the series will remember the night this puppy was conceived, but Chet has no such memory, only a sense of responsibility for the little guy. To escape a dangerous situation, Chet takes a "less gentle approach" to making Shooter follow him, "although [Shooter] did most of his following from in front." Chet reflects, "My less gentle approach had taken something out of me, kind of strange" (260). Is Spencer Quinn laying the groundwork for "Chet and Bernie: The Next Generation?"

Scents and Sensibility cuts closer to the emotional bone than any of these novels since The Dog Who Knew Too Much got deep into the agonies of a bullied adolescent. Characters we learn to like turn up dead; relationships we enjoy are at stake. As sometimes happens in these books, Chet is separated from Bernie, and we come close to losing hope. But, then, Chet pulls us through, as when he fails in "way beyond two" attempts to escape -- "When it comes to numbers, I stop at two," he explains -- and he crawls back to shelter: "[I]t didn't mean I'd stopped trying to be free. I was just taking a break. We took breaks at the Little Detective Agency, just another feature of our business plan" (250).

I've heard a crime novelist on NPR -- Elmore Leonard, I think -- say that "you can kill off anyone you like, but don't kill the dog: the readers will never forgive you." (Author David Rosenfelt offered the same advice at his website back in 2004.) I'm not spoiling anything to say that, when I put this book down, I immediately did what Bernie does just before the glorious mayhem of the final showdown: I knelt by my dogs to give them both a big hug.

[See reflections on the whole Chet and Bernie series, and on other series as well, at my Crime Fiction page.]

Chet keeps up an internal monologue that never gets old. Chet made me smile on every page, and I often laughed out loud, as when he explains how to open a locked door, "something Bernie and I had been working on. You slide the bolt open with your paw and then get a steak tip: that's all there is to it. Give it a try sometime" (186). After this, the eighth book in the series, why shouldn't Chet and Bernie just keep going and never ever stop?

Still, author Spencer Quinn signals early on that this series may be reaching a climax. For the first time, Bernie's neighbors, the Parsons (and little dog Iggy), are integral to the plot, bringing the story literally close to home. Their sorrow and humiliations feel real, as Bernie investigates their son's ties to kidnapping, drug dealing, murder, and, incidentally, the uprooting of legally protected cacti. A corrupt policeman named Mickles, who calls Bernie his "nemesis," shows up early and often, leading us to expect some kind of final showdown. There are moments of doubt when Bernie wonders aloud if he's suffering early onset dementia, and the signs are there.

Then, there's the emergence of Shooter, a puppy who looks and smells a lot like our narrator. Longtime readers of the series will remember the night this puppy was conceived, but Chet has no such memory, only a sense of responsibility for the little guy. To escape a dangerous situation, Chet takes a "less gentle approach" to making Shooter follow him, "although [Shooter] did most of his following from in front." Chet reflects, "My less gentle approach had taken something out of me, kind of strange" (260). Is Spencer Quinn laying the groundwork for "Chet and Bernie: The Next Generation?"

Scents and Sensibility cuts closer to the emotional bone than any of these novels since The Dog Who Knew Too Much got deep into the agonies of a bullied adolescent. Characters we learn to like turn up dead; relationships we enjoy are at stake. As sometimes happens in these books, Chet is separated from Bernie, and we come close to losing hope. But, then, Chet pulls us through, as when he fails in "way beyond two" attempts to escape -- "When it comes to numbers, I stop at two," he explains -- and he crawls back to shelter: "[I]t didn't mean I'd stopped trying to be free. I was just taking a break. We took breaks at the Little Detective Agency, just another feature of our business plan" (250).

I've heard a crime novelist on NPR -- Elmore Leonard, I think -- say that "you can kill off anyone you like, but don't kill the dog: the readers will never forgive you." (Author David Rosenfelt offered the same advice at his website back in 2004.) I'm not spoiling anything to say that, when I put this book down, I immediately did what Bernie does just before the glorious mayhem of the final showdown: I knelt by my dogs to give them both a big hug.

[See reflections on the whole Chet and Bernie series, and on other series as well, at my Crime Fiction page.]

Friday, July 03, 2015

Justice and Love: Christian Democracy

Writing the majority opinion in the Obergefell decision, Justice Kennedy concluded that "marriage embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, sacrifice and family," and that, in marriage, two people "become something greater than they once were."

Republican presidential hopeful Mike Huckabee called the ruling "unjust" because it contravenes the wills of voters in certain states. Perhaps Huckabee doesn't recall how the first Republican President campaigned on the principle that human rights aren't up for vote. Regardless, Huckabee went on to cite Martin Luther King, Jr.'s call in the "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" to resist "unjust" laws.

In his "letter," really a scholarly essay, King addresses fellow clergymen who thought his challenges to Jim Crow ordinances recklessly provocative. Citing ancient church fathers Augustine and Aquinas, King writes that an unjust law is no law at all. To judge a law's "justness," King uses, not votes, not even the Bible, but human dignity as the measure, writing, "Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust." Because King goes on to specify laws that deny common rights to a class of citizens, I wonder if Huckabee has read King's "letter." (I'm not alone. See "Mike Huckabee Should Read..." at The Daily Kos.)

To "uplift" a human personality is one definition of "love." That's how Christian psychologist M. Scott Peck wrote of love in The Road Less Traveled, as one's exertion to encourage and assist in the growth of another. This definition of "love," focused on action instead of feeling, is most practical for covering Jesus' strongest mandates to "love your neighbor as yourself" and to "love your enemy." Justice Kennedy's emphasis on love's power to make individuals "something greater than themselves" shows his use of "love" to be compatible. King advises breaking laws in a "loving" manner, eschewing violence, refusing to be baited into anger, accepting the consequences. In another context, he wrote how this loving resistance would, in Peck's terms, assist in the growth of his opponents:

Do to us what you will and we will still love you.... But be assured that we'll wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom. We will not only win freedom for ourselves; we will [so] appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory. (King, Christmas sermon, December 1967)

King, by imagining love for an individual opponent expanded to encompass a society, anticipates the use made of the word "justice" by the Center for Public Justice (cpjustice.org), an evangelical Christian think tank that influenced my thinking back when it and I were young, around 1980. One of their publications argued from Scripture that "justice" is to society what "love" is to the individual, and both are God's mandate.

For CPJ, a truly Christian democracy in America would reject our Founders' blithe faith, which was never a faith in the Apostle's Creed, but faith in "reason." From George Washington to The Federalist Papers, our founders trusted that reasonable legislators could in any case reach agreement on what constituted "the common good." But the CPJ recognizes that "reasonable" people of good will often start from different premises, both cultural and religious. To require the individual Roman Catholic, Native American, Jew, Muslim, atheist, or Evangelical Christian to set aside their worldviews when making political choices is unloving; to run politics in such a way that people of the dominant worldview needn't take into account voices in the minority is unjust.

Here's a succinct statement of purpose from an essay called "What distinguishes the Center for Public Justice?":

No nation or state may claim to have instituted God's rule in a way that justifies casting out or treating unfairly citizens who disagree with the government-established faith. On biblical terms we believe that God's purposes revealed in and through Jesus Christ call for neither church-governed societies nor governments that give a privileged public place to Christians. Rather, a Christian-democratic approach recognizes that God through Christ is upholding and renewing human responsibility on earth, including the responsibility to govern. And since ...Christ did not call his disciples to try to establish God's kingdom by force, human governance requires the just and equal treatment of all citizens. (Link to this essay at the CPJ website)

On the issue at hand, even reasonable Christians of good will disagree. (See the web site Religious Tolerance for an even-handed survey of Bible-based responses to homosexuality.) In fact, I disagree with the position on same-sex marriage outlined at CPJ's web site.

Although the CPJ reaches a different conclusion than I do, their approach is nonetheless the best way to ensure a truly democratic society. As my friend philosophy professor Susan Rouse points out, "There's a lot more to being a democratic society than voting. Even Stalin was re-elected." In a nutshell, here's the CPJ's critique and their answer:

Politics [in the US today] often amounts to little more than interest-group competition among diverse groups, each seeking its own goals. Too little attention is given to the soundness of public institutions, to the art of long-term constitutional statecraft, and to the common good of the republic as a whole. ...The Center believes that the public good of the American commonwealth, which is shared by all citizens, can flourish only when governed by standards that transcend interest-group competition. (link)I'm so often put off by the ugly competition among the parties in America. Now that I've re-discovered the CPJ, I'll look to them for some level-headed, long-range, loving responses to the issues of the day.

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Agatha Christie Reflects in The Mirror Crack'd

So well does the cover capture a critical moment of Agatha Christie's The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side (Penguin edition), that the image ought to bear a "Spoiler Alert."

No actual mirrors were destroyed in the making of this book, however. The title derives from Tennyson's verse about a woman who, taken by a premonition, looks "as if a mirror crack'd." In Christie's novel, witnesses describe a movie star's look of "doom" when she freezes during a tedious anecdote told by a village woman at a PR fete. The star has apparently seen someone or something beyond the reception line. Minutes later, that villager has been poisoned. The villager had swallowed a cocktail poured for her host, so the conclusion is obvious: Someone had intended to kill the diva. The key seems to lie in whatever the actress saw that caused her to freeze.

But a theme of mirrors seems to run through the novel, beginning with the narcissism of the actress. The diva's doctor says that film stars, while "obsessed with themselves," are far from "conceited," instead being fearful of their own "inadequacy" (Kindle edition, 80). Given that the novel is dedicated to Margaret Rutherford, who was portraying Christie's detective "Miss Marple" in a series of films still ongoing when Christie wrote this novel in 1962, Agatha Christie may have been writing from fresh personal experience.

Motivated by her narcissistic desire to be generous, the diva Marina Gregg adopted children. She soon lost interest, leaving behind a bitterness that one of the grown children describes this way: "[Marina Gregg] did the worst thing to me that anyone can to anyone else. Let them believe that they're loved and wanted, and then show them that it's all a sham" (148).

Another narcissist is the unfortunate victim Heather Badcock, a community leader in the new housing developments outside Jane Marple's beloved little town. Miss Marple recognizes her type:

Miss Marple herself is hemmed in during this story by a cheerfully domineering live-in nurse, "full of kindness, ready to feel affection for her charge" but treating Miss Marple "as a mentally afflicted child" (6).

Aside from these narcissists who see themselves reflected in the world, Dame Agatha works "mirrors" into the fabric of her novel in other ways. Miss Marple several times makes a point of holding up the mirror of the past to characters in her present, satisfied to confirm that "human nature" doesn't change. The housing developments that bring hordes of younger families to the town seem at first to threaten Miss Marple's sense of life there, until she recognizes "types" from her own childhood among the busty teenaged girls chatting up boys on the sidewalk. Curious about the movie star, Miss Marple reads movie magazines and observes that all the gossip is only what we find in any "specialized" and insular environment, such as a hospital.

Not to give away too much, Miss Marple figures out whodunit when she looks at the events of the fatal cocktail party as through a mirror. From a reverse perspective, she says, it all becomes so obvious.

Dame Agatha kept the jump on this reader throughout The Mirror Crack'd... Every time I made a note along the lines of, "Ah-ha! This person is really so - and - so," or, "That photograph will prove something," my prize revelation was raised within a couple of pages and dismissed as so much red herring.

While the plot drew me forward, I was pleased to stay in the world of this book awhile, recognizing a mirror for my own reality in the ways that Miss Marple pushes back against the constricting horizons of old age.

Because I wanted to linger in that world, I downloaded the 1980 film made of this novel, starring Elizabeth Taylor as the actress, Kim Novak as her rival, Rock Hudson as her adoring husband, and Angela Lansbury as the elderly Miss Marple. I almost wish I hadn't done so. At the time -- a couple years before she starred in the TV series Murder, She Wrote -- Lansbury was under 50 and vigorous, starring in SWEENEY TODD on Broadway (where I'd just seen her, myself). Even in the publicity shots, she looks like a high school drama club's idea of an old lady. The film lacks that undercurrent of loss and resentment that gives subtext to Christie's novel. Then, the creators suspend story to give their Hollywood stars ample opportunity to cut each other with jokes about wigs, weight, agents, and sex. They're all such caricatures in the first half of the movie that the second half fails, though the actors try valiantly to make us take their emotions seriously.

The movie's two standouts played the victim and the actress's secretary. The doomed "Heather Badcock" comes across oblivious as Christie describes her, but also surprisingly appealing, vivacious and happy, played by Maureen Bennett in what appears from a cursory web search to have been her first and last film. The diva's secretary, whose love for her employer's husband is a poorly-kept secret, is played with much repressed passion and resentment by Geraldine Chaplin. She often appears to be simultaneously officious, tearful, lustful, and allergic.

By the way, Wikipedia points out many parallels between the fictional diva and the real-life star Gene Tierney. In 1962, like "Marina Gregg," Tierney was trying for a comeback from years of breakdown and health problems. In Tierney's memoir, published in 1978 (two years after Christie's death), Tierney reveals an incident from her early career that is identical to the secret revealed in The Mirror Crack'd.... But how could Christie have written of this private, tragic incident, sixteen years before the memoir was published? It's a mystery.

[See my Crime Fiction page for links to my reflections on works by Agatha Christie, P.D.James, and many others.]

No actual mirrors were destroyed in the making of this book, however. The title derives from Tennyson's verse about a woman who, taken by a premonition, looks "as if a mirror crack'd." In Christie's novel, witnesses describe a movie star's look of "doom" when she freezes during a tedious anecdote told by a village woman at a PR fete. The star has apparently seen someone or something beyond the reception line. Minutes later, that villager has been poisoned. The villager had swallowed a cocktail poured for her host, so the conclusion is obvious: Someone had intended to kill the diva. The key seems to lie in whatever the actress saw that caused her to freeze.

But a theme of mirrors seems to run through the novel, beginning with the narcissism of the actress. The diva's doctor says that film stars, while "obsessed with themselves," are far from "conceited," instead being fearful of their own "inadequacy" (Kindle edition, 80). Given that the novel is dedicated to Margaret Rutherford, who was portraying Christie's detective "Miss Marple" in a series of films still ongoing when Christie wrote this novel in 1962, Agatha Christie may have been writing from fresh personal experience.

Motivated by her narcissistic desire to be generous, the diva Marina Gregg adopted children. She soon lost interest, leaving behind a bitterness that one of the grown children describes this way: "[Marina Gregg] did the worst thing to me that anyone can to anyone else. Let them believe that they're loved and wanted, and then show them that it's all a sham" (148).

Another narcissist is the unfortunate victim Heather Badcock, a community leader in the new housing developments outside Jane Marple's beloved little town. Miss Marple recognizes her type:

[Heather Badcock] is self-centred, and I don't mean selfish by that.... You can be kind and unselfish and even thoughtful [but] never really know what you are doing. ...Life [for people like this] is a kind of one-way track -- just their own progress through it. Other people seem to them just like -- like wallpaper in the room. (50)

Miss Marple herself is hemmed in during this story by a cheerfully domineering live-in nurse, "full of kindness, ready to feel affection for her charge" but treating Miss Marple "as a mentally afflicted child" (6).

Aside from these narcissists who see themselves reflected in the world, Dame Agatha works "mirrors" into the fabric of her novel in other ways. Miss Marple several times makes a point of holding up the mirror of the past to characters in her present, satisfied to confirm that "human nature" doesn't change. The housing developments that bring hordes of younger families to the town seem at first to threaten Miss Marple's sense of life there, until she recognizes "types" from her own childhood among the busty teenaged girls chatting up boys on the sidewalk. Curious about the movie star, Miss Marple reads movie magazines and observes that all the gossip is only what we find in any "specialized" and insular environment, such as a hospital.

Not to give away too much, Miss Marple figures out whodunit when she looks at the events of the fatal cocktail party as through a mirror. From a reverse perspective, she says, it all becomes so obvious.

Dame Agatha kept the jump on this reader throughout The Mirror Crack'd... Every time I made a note along the lines of, "Ah-ha! This person is really so - and - so," or, "That photograph will prove something," my prize revelation was raised within a couple of pages and dismissed as so much red herring.

While the plot drew me forward, I was pleased to stay in the world of this book awhile, recognizing a mirror for my own reality in the ways that Miss Marple pushes back against the constricting horizons of old age.

Because I wanted to linger in that world, I downloaded the 1980 film made of this novel, starring Elizabeth Taylor as the actress, Kim Novak as her rival, Rock Hudson as her adoring husband, and Angela Lansbury as the elderly Miss Marple. I almost wish I hadn't done so. At the time -- a couple years before she starred in the TV series Murder, She Wrote -- Lansbury was under 50 and vigorous, starring in SWEENEY TODD on Broadway (where I'd just seen her, myself). Even in the publicity shots, she looks like a high school drama club's idea of an old lady. The film lacks that undercurrent of loss and resentment that gives subtext to Christie's novel. Then, the creators suspend story to give their Hollywood stars ample opportunity to cut each other with jokes about wigs, weight, agents, and sex. They're all such caricatures in the first half of the movie that the second half fails, though the actors try valiantly to make us take their emotions seriously.

The movie's two standouts played the victim and the actress's secretary. The doomed "Heather Badcock" comes across oblivious as Christie describes her, but also surprisingly appealing, vivacious and happy, played by Maureen Bennett in what appears from a cursory web search to have been her first and last film. The diva's secretary, whose love for her employer's husband is a poorly-kept secret, is played with much repressed passion and resentment by Geraldine Chaplin. She often appears to be simultaneously officious, tearful, lustful, and allergic.

By the way, Wikipedia points out many parallels between the fictional diva and the real-life star Gene Tierney. In 1962, like "Marina Gregg," Tierney was trying for a comeback from years of breakdown and health problems. In Tierney's memoir, published in 1978 (two years after Christie's death), Tierney reveals an incident from her early career that is identical to the secret revealed in The Mirror Crack'd.... But how could Christie have written of this private, tragic incident, sixteen years before the memoir was published? It's a mystery.

[See my Crime Fiction page for links to my reflections on works by Agatha Christie, P.D.James, and many others.]

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Musicologist Analyzes How Sondheim Found his Sound

|

| [Photo: Mandy and Madonna sing "What Can You Lose?"] |

Diehard Sondheim Fan Club member since 1974, I still have to admit that I cannot hum some of Stephen Sondheim's songs. Musicologist Steve Swayne explains why. He also explains why that's a good thing.

Swayne borrows a phrase from a Sondheim lyric to explain that "Sondheim's melodies often start out like songs," but then show a "remarkable degree of motivic compression" (Swayne 103). Swayne demonstrates what he means in fifteen pages analyzing one short ballad, "What Can You Lose?" from the Disney film Dick Tracy (1990). He traces every phrase of the tune to the first "motif," four notes sung by the character "88 Keys" (Mandy Patinkin). This one motif appears "no fewer than twenty-eight times" in just 30-odd measures of singing. Sometimes the four note phrase repeats a note, or jumps up instead down. so that "the song becomes difficult to remember precisely; one must make a concentrated effort to commit its melodic nuances to memory." Having tried and failed many times to sing this song in the car, I can second that.

For comparison, Swayne tells how "hummable" songwriters introduce two or three different motifs early. Even in the motif-driven song "Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered," composer Richard Rodgers combines the motif of an upward scale with the three-note motif repeated on the syllables "wild again," "(be)guiled again," "simpering," etc. Rodgers goes on to invert the pattern at the bridge. Sondheim can write that way too; Swayne gives "Anyone Can Whistle" as an example of a tune built from a variety of ideas.

But Sondheim most often works with just one motif. Why? From early in his musical education, Sondheim aimed for "the quality indigenous to the best art: maximum development of the minimum of material" (Sondheim, lauding songs of Jerome Kern, 53).

Besides, as Swayne demonstrates with "What Can You Lose?" Sondheim can vary a single motif to express characters' thoughts and feelings. In a way, he's using the music to act the part.

Swayne starts his book with Sondheim's explanation, "I've discovered that... essentially I'm a playwright who writes with song, and that playwrights are actors" (1). So, for "What Can You Lose?" the character 88 Keys is seated at a piano late at night beside the woman he secretly adores, and the piano accompaniment therefore sounds improvised, ruminative. The first four notes pick up on the rhythm and inflection of a phrase in the dialogue just completed: "What can you lose?" Swayne demonstrates numerous ways that the four-note motive varies to show rising hope as "88" imagines telling her his feelings, while, throughout, the piano accompaniment says something different:

But its rhythmic emphases off the beat... its doubling in the soprano and tenor voices, and its descent of a third all convey leadenness of heart and futility of hope. The answer to his titular question is something 88 Keys already knows. When he asks it, the [accompaniment] answers him: you will lose (116).

Midway, the song seems to start over, as "88" begins to imagine another possibility, that she already knows the truth and chooses to ignore it; the motive bends with the character's feelings.

Swayne tells us that Sondheim's songs are "kinetic" (120). There's no repeated "hook" as in rock and pop songs, because those are "inherently undramatic," treading the same emotional territory over and over. Sondheim doesn't often resort to driving rhythmic patterns to move a song forward independent of character, preferring that the forward motion come from developments internal to the character's song.

With this analysis at the core of his book, Swayne packs the rest with what Sondheim learned from his teachers and from classical composers (especially Ravel), from the Broadway masters of his teens (especially Harold Arlen), and from film.

Much of this I've heard before in books about Sondheim from Craig Zadan's Sondheim and Company (1974) onward, and articles in Sondheim Review. Here are some fun bits that are new to me, or, at least, newly remembered:

- Sondheim borrows a technique that he described in a student paper on Ravel, that of re-harmonizing the accompaniment under a motif that repeats, unvaried, as under the phrase "Finishing the hat..." (19)

- The first notes sung in "Send in the Clowns" are an inversion of a motif in the "theme" from A Little Night Music, the one sung to the words, "Five o'clock...Six o'clock..." etc.

- The "follies" dream numbers for the four main characters in Follies are derived from "book" songs they sang in character earlier in the show; and the accompaniment of "Sally's" song "Losing My Mind" is inverted to make the accompaniment for the song of her counterpart "Phyllis" in "Lucy and Jessie."

- The five-note "bean theme" in Into the Woods strikes again, in the song "No One Is Alone": inverted, they are the notes of the song's bridge section, beginning, "People make mistakes."

- Hard to believe: Sondheim remembers that Bernstein faulted him for sticking "wrong notes" such as the augmented fourth (or "tritone") in his music -- presumably to show off his sophistication. Sondheim pointed out that "I Feel Pretty" is the one song in West Side Story that does not contain the tritone. Now, I knew that; but I'm shocked to read that Bernstein was shocked (91).

- Sondheim taught Bernstein how to add a "thumb line" in the 2/4 measures of the introductory verse to "Something's Coming" in West Side Story. I knew that, but I didn't notice that Bernstein went on to base the rest of the song on that same "thumb line." (92) (Now, this is embarrassing, because I've known that song well since 1964.)

- Sondheim was excited by the possibility that three characters' three songs at the start of A Little Night Music could all go together, but he didn't want the audience to see it coming. To make it work, he says, he filled the chords of the third song "Soon" with sixths and fourths, so the accompaniment would be "like spaghetti sauce -- it'll cover almost anything" (251).

- About how he based the entire score of Anyone Can Whistle on two intervals (played by the first four notes of the Overture), Sondheim admits that the audience probably wouldn't hear "the seeds" of the songs, except maybe subliminally. But the technique "helped me to write the score"(245)

- Swayne uses the song "Putting it Together" to demonstrate how Sondheim has found musical ways to achieve cinematic effects -- cross-fades and tracking shots, as when we follow the character "George" through the sung dialogue of ten other characters.

[See my Sondheim page for many other reflections on matters relating to Sondheim, his shows, and musical theatre more generally.]

Source

Swayne, Steve. How Sondheim Found His Sound. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Saturday, June 20, 2015

Mozart, Eminem 'n' Me

When you take the words out of rap, you're left with a form that Mozart would recognize instantly.

I discovered this when a student's family won my service as composer in the school's recent auction. The boy wanted a rap song, but he wanted to play it on piano. He assigned me some research into videos by Eminem and Lil Wayne.

I noted this structure to the pieces that I heard:

I noticed that the rapper squeezes more and more words into four beats as the song progresses.

That's just a Rondo, such as Mozart's Rondo a la Turk: ABACADA, where "A" is the familiar "hook," and B, C, and D are increasingly showy variations over the same root chords.

So, am I the last musician in the world to figure this out, or one of the first?

I discovered this when a student's family won my service as composer in the school's recent auction. The boy wanted a rap song, but he wanted to play it on piano. He assigned me some research into videos by Eminem and Lil Wayne.

I noted this structure to the pieces that I heard:

A "hook," a tune played on instruments the first time, sung later.

Two-to-four stanzas of rapping declaimed over a repeated bass line

Repeat of the "hook"

More rapping, different pattern over the same repeated bass line

Repeat of the hook

I noticed that the rapper squeezes more and more words into four beats as the song progresses.

|

| [Image: page one of rap for piano solo] |

So, am I the last musician in the world to figure this out, or one of the first?

Friday, June 19, 2015

The Manden Charter of 1222:

African Exceptionalism?

A student of mine in 7th grade once proposed to do a researched essay on the question, "When will Africans evolve?" I took her into the hall to make her understand how limited our view of Africa is, and how the assumptions behind her question would be a wedge between her and African American friends. She understood the implications of the word "evolved," then, but still was interested only in researching the poverty and strife that bolstered her preconceptions of Africa as a pitiable land, from her vantage point of Exceptional America.

Today, I heard a report by Ibrahima Diane on the BBC program The Fifth Floor that I thought would open my students' eyes (link to listen). Now that I've done a cursory search of the internet, I'm a little less excited. Still, what I heard is interesting in itself.

From the same time as Magna Carta, we now have the Manden Charter, transcribed from oral history revealed to a French scholar by Malian griots in the 1990s. Because its form was fluid as memory until then, susceptible to influences from modern politics and culture, we have reason to wonder if its contents have not been shaped in part by wishful thinking: Wouldn't it be great to prove that the seminal document of Western democracy had an African twin, arrived at independently?

So, with the caveat that something may have been gained in translation, here's a taste of what I've learned about this Manden Charter:

The document, also known as the Kurukan Fuga, proclaims the rights of individuals, even those held in slavery. The body is only a man's dressing, it says:

So every individual man's rights are to be respected. We are also told not to offend "women, our mothers."

The "Joking relationship" among people of a community is also to be sacrosanct. That is, satire is not actionable, and all are encouraged to laugh at the king. (from a list of articles at the Wikipedia article for Kouroukan Fouga).

Like Magna Carta, some of the Manden Charter's articles refer to immediate concerns at the time of the agreement, such as the decree that "Fakombe is nominated chief of hunters," and fixing the price for a dowry as three cows. Also like Magna Carta, this constitutional document was instantly ignored. Slavery among the Malian people continued, only escalating when Europeans got into the slave trade three centuries later.

I understand from the interview on BBC that this would have been influenced by Islamic teaching, though I see no specific references to the Prophet or to God of Abraham and Jesus. As I'm currently reading Theology for a Troubled Believer by Diogenes Allen, I've been thinking about Allen's claim that the absolute value of the individual is an idea that cannot be derived from anything other than "revealed religion." Philosophers and political theorists since the Enlightenment have tried and failed. Here is the absolute value of the individual asserted in a 13th century agreement, and many more Enlightenment ideals besides.

At the least, the Manden Charter should give pause to anyone who makes much of "American Exceptionalism."

Today, I heard a report by Ibrahima Diane on the BBC program The Fifth Floor that I thought would open my students' eyes (link to listen). Now that I've done a cursory search of the internet, I'm a little less excited. Still, what I heard is interesting in itself.

From the same time as Magna Carta, we now have the Manden Charter, transcribed from oral history revealed to a French scholar by Malian griots in the 1990s. Because its form was fluid as memory until then, susceptible to influences from modern politics and culture, we have reason to wonder if its contents have not been shaped in part by wishful thinking: Wouldn't it be great to prove that the seminal document of Western democracy had an African twin, arrived at independently?

So, with the caveat that something may have been gained in translation, here's a taste of what I've learned about this Manden Charter:

The document, also known as the Kurukan Fuga, proclaims the rights of individuals, even those held in slavery. The body is only a man's dressing, it says:

But his ‘soul’, his spirit lives on three things:

He must see what he wishes to see

He must say what he wishes to sayAnd do what he wishes to do

(translation by Michael Neocosmos, "The Manden Charter," The Franz Fanon Blog)

So every individual man's rights are to be respected. We are also told not to offend "women, our mothers."

The "Joking relationship" among people of a community is also to be sacrosanct. That is, satire is not actionable, and all are encouraged to laugh at the king. (from a list of articles at the Wikipedia article for Kouroukan Fouga).

Like Magna Carta, some of the Manden Charter's articles refer to immediate concerns at the time of the agreement, such as the decree that "Fakombe is nominated chief of hunters," and fixing the price for a dowry as three cows. Also like Magna Carta, this constitutional document was instantly ignored. Slavery among the Malian people continued, only escalating when Europeans got into the slave trade three centuries later.

I understand from the interview on BBC that this would have been influenced by Islamic teaching, though I see no specific references to the Prophet or to God of Abraham and Jesus. As I'm currently reading Theology for a Troubled Believer by Diogenes Allen, I've been thinking about Allen's claim that the absolute value of the individual is an idea that cannot be derived from anything other than "revealed religion." Philosophers and political theorists since the Enlightenment have tried and failed. Here is the absolute value of the individual asserted in a 13th century agreement, and many more Enlightenment ideals besides.

At the least, the Manden Charter should give pause to anyone who makes much of "American Exceptionalism."

Thursday, June 18, 2015

The Rodgers and Hammerstein Touch

|

[Photo: Kelli O'Hara and Ken Watanabe perform "Shall We Dance?" from www.theatermania.com]

Why I was touched, I'm still trying to figure out. I've no prior emotional attachment to Carousel, while the song "Shall We Dance?" from The King and I is over-familiar. Besides, I've always thought that Hammerstein spoke through his character "Nellie" in South Pacific when he had her sing, "They call me a cockeyed optimist," and, "I'm as corny as Kansas in August."

But one man's "corniness" is another man's generosity of heart. Hammerstein ends Carousel with a country doctor's advice to graduates of a small-town high school, including this: "Don't worry if other people don't like you; you try to like them." Hammerstein digs to appreciate what's good in his characters, Carousel's volatile leading man Billy Bigelow a prime example. Earlier, the ingenue sang, with Billy in mind, "What's the use of wond'ring / If he's good or if he's bad?.. / ...You love him... / There's nothing more to say." Composer Richard Rodgers inserts a long pause before that last line, musically surprising, dramatically expressive of the character's inexpressible feeling.

The spirit of Billy Bigelow, killed before his daughter was born, urges his grown daughter to listen to the speaker, who goes on to promise the graduates that, whatever crises they face, "You'll never walk alone." Cue orchestra, cue chorus reprising that promise, cue copious tears. We're in Hammerstein's world, and we want to believe that everyone who has loved us, though they're gone, is still at work in us; we want to believe that it's possible to hold on to the good when we face the bad. We want to learn from Billy Bigelow not to die without saying the things we want to say to our loved ones. It's the kind of sentiment mocked in the ad, "I love ya', man." But that doesn't make it less real.

"Shall We Dance?" on the other hand, is a sophisticated piece of theatre, without leaning on irony or detachment. The song comes late in the show, when the governess Anna, alone with the King of Siam, answers his questions about courtship in England.

Anna and the King have come to represent Western Liberalism and Eastern Tradition, and have gained respect for each other. Their battles of will have often been funny, but we know that Anna is secretly involved in a life-and-death matter involving one of the King's many slave-wives. We also know from an earlier song that Anna's description of young lovers comes from memory of her late, beloved husband. All of this subtext goes into a song that appears to be so simple. Anna sets the scene:

We've just been introduced.

I do not know you well.

But when the music started

Something drew me to your side.

So many men and girls

Are in each others' arms.

It seems to me we might be

Similarly occupied.

That formality of the last two lines, punctuated by inner rhyme and end rhyme, makes us smile. Then, Anna sings the refrain, miming the action. The words fly off into images of romantic fantasy, come back to earth for a little business formality -- "on the clear understanding that this kind of thing can happen" -- before three repetitions turn "Shall we dance?" from polite interrogative to imperative.

Shall we dance?Holding hands up but apart, Anna instructs the King, who repeats the refrain with her, getting a laugh when he tries to count "1,2,3, and...."

On a bright cloud of music,

Shall we fly?

Shall we dance?

Shall we then say "good night"

And mean "good-bye?"

Or perchance,

When the last little star has left the sky,

Will we still be together

With our arms around each other

And will you be my new romance?

On the clear understanding

That this kind of thing can happen,

Shall we dance?

Shall we dance?

Shall we dance? (lyric by Oscar Hammerstein III)

The moment that gets to me (even now, while I type this) is what we saw on screen at the Tonys. The King

stops the lesson to demand that Anna dance with him the way he's seen it done, hands clasped, bodies close. Rodgers's music swells to launch the two around the vast stage with joyful abandon. It's a moment that can't last: Anna's help to the slave is an affront to the King's authority that will shame him and destroy him.

So much is packed into that moment when they stop singing, join hands, and cover the entire stage with their dance: it's dramatic poetry.

On the Tonys broadcast, the song was a beautiful moment that stood out among the co-hosts' ironically retro banter, all bad puns and innuendo; and ads that played on cute sentiment, sexuality, and desire for status to sell us products.

Really, a few minutes in Rodgers' and Hammerstein's "corny" world may make us weep for ours.

[See my Sondheim page for many other reflections on matters relating to Oscar Hammerstein's protege Stephen Sondheim, and musical theatre more generally.]

Sunday, June 14, 2015

Agatha Christie's Miss Marple At Bertram's Hotel

As my friend Susan Rouse points out, nostalgia is built into the whole Jane Marple series. Most of the stories take place in Miss Marple's little town post-World War II, a time for loss of empire, domestic displacement, and learning of a new normal. "Much of her life had...to be spent recalling past pleasures," Christie writes (220).

Here, nostalgia is the point. Miss Marple on holiday is merely one of a half-dozen denizens of an old London hotel who get our attention. Through description and dialogue, Christie makes much of the hotel's preservation of forms and manners of the pre-war era. Miss Marple hardly speaks of anything else, and mostly hangs in the background of others' stories. We see a glamorous and scandalous jet-setter, American tourists, some old military men and clergymen. A race-car driver in black leather appears. But all are measured against the good old-fashioned qualities of the quaint hotel and its staff. The common sentiment that Bertram's is all too good to be true turns out to be a point of the plot.

Here, nostalgia is the point. Miss Marple on holiday is merely one of a half-dozen denizens of an old London hotel who get our attention. Through description and dialogue, Christie makes much of the hotel's preservation of forms and manners of the pre-war era. Miss Marple hardly speaks of anything else, and mostly hangs in the background of others' stories. We see a glamorous and scandalous jet-setter, American tourists, some old military men and clergymen. A race-car driver in black leather appears. But all are measured against the good old-fashioned qualities of the quaint hotel and its staff. The common sentiment that Bertram's is all too good to be true turns out to be a point of the plot. We don't get a body until more than two-thirds of the way through the novel, though Christie throws in a single chapter early on to let us know that criminals use the hotel as a front. Bertram's Hotel truly is "too good to be true."

Instead of investigating crime, we're following the actions of teenaged girls, one mischievous, the other cautious; and a clergyman pretty far along on the road to dementia. Their foibles are not treated as serious. Adults observing the girls comment that one expects girls that age to lie about having improper boyfriends, and Canon Pennyfather's confusions are presented as endearing.

But Christie does suggest that the loose morals of the day are a sign of underlying evil. The scandalous jet setter Lady Sedgwick comments, appropos her own marriage, "Plenty of adultery nowadays. Children have to learn about it, have to grow up with it" (2450). Speculating on the whereabouts of Canon Pennyfather, a policeman remarks, "Doesn't sound as if [the priest had] gone off with a choirboy" (1420), a line thrown away as if pederasty has become just one of those things to expect. Permissive guardians and teachers are all "too nice" to the mischievous girl, observes a senior detective, but not Jane Marple. He says she has "had a long life of experience in noticing evil, fancying evil, suspecting evil and going forth to do battle with evil" (2472). Marple reflects sadly that the French adage works as well in reverse, "Plus c'est la meme chose, plus ca change," as she has observed that the moral underpinnings have changed even where the forms have been maintained (2845).

Christie gives Miss Marple credible reasons to be in just the right places at the right times to witness clues. Miss Marple just happens to be knitting in a high-backed chair of the hotel's writing room to overhear a certain conversation; happens to be in cafes not once, but twice, where she sees the race driver's assignations with women; happens to awaken around 3 a.m. to investigate a noise in the hall that turns out to be criminal activity. While each incident is credible in itself, this reader just had to suspend disbelief in the interest of enjoying the whole.

Funny, Miss Marple in 1965 was looking back fondly on a more innocent time forty years or so earlier; in 2015, it's been forty-five years since I read At Bertram's Hotel at the Sandy Springs Library, and, even then, in the post-Beatles Seventies, I was already nostalgic for the London of Diana Riggs's Avengers series and Petula Clark. I know how Jane Marple feels. I also agree with Dame Agatha, that a murder mystery is a great framework for social commentary.

[See my Detective Fiction page for capsule book reviews and links to reflective essays.]

Sunday, June 07, 2015

Canine Comedy Sylvia: How We Project onto our Pets

|

| [Photo: Mia's eye says,"Can't I have breakfast in bed?" or am I just projecting?] |

A.R.Gurney's comedy Sylvia starts from a bold conceit: a grown woman portrays "Sylvia" the dog (Amanda Crucher) as a biped in jeans who speaks aloud the kinds of thoughts that we dog owners attribute to our pups. Instead of barking, she says, "Hey! Hey!" Instead of wearing the leash, she holds it. She tells "Greg," her middle-aged rescuer (James Baskin), "I love you! You are my God!" When Greg's wife "Kate" finds her husband enthralled by the dog, we don't blame Kate for being jealous.

The story seems to come down to one question: will Greg choose Sylvia over Kate? At Stage Door Players' production north of Atlanta, the cast rode a steady stream of laughs before they reached Gurney's surprising resolution.

Director Shelley McCook writes in the program that she sees a larger, more universal crisis in the play. She herself portrayed "Sylvia" in the first production I saw years ago, and naturally understood the play to be dog-centric. But, as she points out, Greg and Kate, their children away at college, now "begin to explore previously overlooked dreams, ambitions, and longings," a moment that challenges their marriage of twenty years. "The introduction of a 'younger woman' is only a catalyst for the conflict that emerges from this new and uncertain phase of their lives."

Perhaps because McCook herself, script in hand, subbed as "Kate" on the night that I saw the show, "Kate's" agonies stood out more than in other productions I've seen. As the couple consult friends and a therapist (all played convincingly by actor Doyle Reynolds), one important thought emerges, that "Greg" is projecting on "Sylvia." A character at the dog park warns Greg away from using a human name for a dog: "You'll forget she's just a dog." The therapist suggests that a middle-aged man, no longer providing for children, is seeing in his dog's eyes all the adoration that he needs to see, to feel important.

Since I saw the play, I've looked more deeply into my dogs' eyes. Am I wrong to see adoration in the eyes of my adolescent Mia? When I see through a screen to my old dog Luis sitting at the top of steps that he used to climb at a gallop, am I wrong to read wistfulness into that face?

|

| [Photo: Luis, through window screen, unaware of me] |

Friday, June 05, 2015

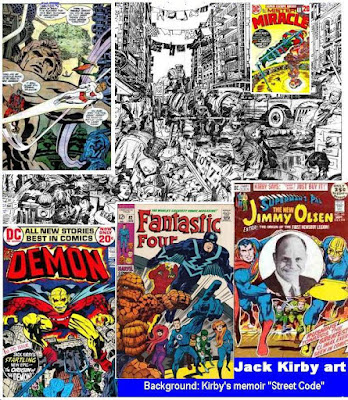

Jack Kirby: "King of Comics" Exploded the Panels

"Kirby is coming!"

This promotional tag printed in some DC comics in the early 1970s made me uneasy. At age eleven, I liked DC the way it was, uncrowded panels stepping us through the story from upper left to lower right, and its stories ending with bad guy in jail, hero in civilian clothes, life restored to normal until the next month's issue.

Jack Kirby cracked open my comic book world, as he had been doing since comics were new. Cartoonist Jules Feiffer wrote of Kirby's collaborations with Joe Simon in the 1940s, "Every panel was a population explosion -- casts of thousands: all fighting leaping, falling, crawling...Speed was the thing, rocking, uproarious speed" (Feiffer in Evanier, 49).

In the 1960s, with Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and others at DC's rival company, Kirby developed what came to be known as the "Marvel Universe," where characters' actions in one comic book had repercussions in another; a super-being such as the Hulk or Silver Surfer could be a hero in one context and a threat in another; a guy's personal problems didn't end when he put on his tights. Happy endings? Forget about it!

The Marvel model seemed chaotic and pretty depressing to me, so I remained wary when Kirby titles started to show up in the revolving comics rack at the drug store. But Kirby had created a meta-story for our world that had already involved my favorite DC characters: we learned that the corporation buying the Daily Planet was a front, making of Clark "Superman" Kent an unwitting employee of the evil lord in Kirby's inter-planetary cold war between New Genesis and Apokolips.

I surrendered to Kirby's vision, as did fantasy writer Neil Gaiman:

I learned to appreciate Kirby's damn-the-perspective, full-speed-ahead approach to drawing. His hobby of making photo collages may be a key to his style. Abstracted from their original context in photographs and pasted in a jumble, forms lose their function, and perspective vanishes; but odd juxtapositions draw the eye and challenge the imagination to make its own sense. See what I mean in the memorable spread from New Gods #1 pasted in the upper-left hand corner of my little collage of Kirby drawings created for this blog. Long curves, jagged lines, some kind of colossal statue, some disconnected machinery, some background silhouettes, together make no architectural sense, but all suggest a magnificent unearthly city. Biographer Mark Evanier comments about Kirby's collage-making,

The black-and-white drawing in the background of my collage is part of "Street Code," Kirby's memoir of childhood, left unfinished in 1983 when his eyes made drawing nearly impossible. Mark Evanier's biography of Kirby, King of Comics, prints the whole thing in its rough penciled state, including distortions due to Kirby's eye trouble. But the two-page spread (see it online) is itself a collage of impressions recalled from the Lower East Side in the early 1920s, remarkable as anything else he ever drew. Kirby jumbles together glimpses of dozens of individuals all engaged in their own stories.

Kirby's own "spin on the American Dream," according to biographer Mark Evanier, was, "You make your boss rich and he'll take care of you." Evanier, who met Kirby around the time that the artist quit Marvel to move to DC, observes, "All Jack's life he believed in that, no matter how many times the bosses got rich and he didn't" (37). Exhibit A is "The Incredible Hulk Poster" that came to symbolize for Kirby what he saw as Marvel's lack of consideration for Kirby's work. "He'd created something that was potentially profitable... but he hadn't received a cent and someone else's name was signed to work that was essentially his" (159).