- Related links

- I respond to the second book in Mullen's Darktown series, Lightning Men.

- See my Crime Fiction page for a curated guide to other fiction in the genre.

- My reflection on the movies Chinatown and LA Confidential (07/2016) specifically focuses on "noir" crime fiction. It ends with links to other reflections that explore the noir approach to storytelling, including the series by wonderful Walter Mosley about Easy Rawlins, a black man pursuing justice in LA after the Second World War.

- In an interview with NPR's Karen Grigsby Bates, Mullen tells her that he'd already started the novel in 2014 when the police killing of Michael Brown made headlines. When Bates asks if a white author Thomas Mullen can write a fair account of the black experience, he tells how the manuscript was sent around without his name or any mention of his previous historical novels, so that the story was accepted on its own merits. Hear the interview with Mullen and his publisher, 9/23/2016

- The image of Atlanta, ca. 1948, is from a blogger's review of the hardback edition at Jolene Grace Books

Thursday, June 25, 2020

"Darktown": Good Cops, Bad Cops, and Race in Atlanta, 1948

Tuesday, June 23, 2020

"Ashes": Seeds of America Trilogy Concludes

Yet the overarching question of the novel gives it the energy and delight of a romantic comedy: Will Isabel and Curzon ever realize that they love each other?

My friend Susan started reading this third book while I was still enjoying Forge, which is narrated by the young man Curzon (see "Friendship and Fire," 06/2020). I expressed my hope that Curzon's affable narrative voice might continue in the final book, or at least alternate chapters with Isabel's more intense voice. Susan made an interesting comment: "The narrator has to be Isabel, because she has more to learn."

I agree. When Curzon wants to re-enlist with the Continental Army, Isabel tries to dissuade him:

"I am my own army," I said. "My feet and legs, my hands, arms, and back, those are my soldiers. My general lives up here" -- I tapped my forehead -- "watching for the enemy and commanding the field of battle.... Neither redcoats nor rebels fight for me. I see no reason to support them." (126)Curzon asks, "What do you fight for, then?" She answers that she wants only to get away from fighting. But, weeks later, she comes to understand an essential difference in their approaches to life:

He favored the larger stage, the grand scale at which folks sought to improve the world. I had chosen to focus on the smaller stage, concentrating myself only with my sister's circumstances.... I realized that Curzon did not care more for his army than me, or even feel that there was a choice to be made. His heart was so large, it could love multitudes. And it did. (242)

Isabel learns from Curzon. She speaks to both the larger and smaller "stage" when, following victory, Virginians re-enslave blacks in the camp and in the ranks. When Curzon expresses bitterness, she pours seeds into Curzon's hand, the ones from her late mother's garden that Isabel and Curzon have preserved through all their years together. A garden has to begin with something, she explains. As the seeds sprout and bloom, you can tend and shape the garden. Echoing the very first words of the series, a quote from Thomas Paine, Isabel says, "Seems to me this is the seed time for America" (271).

We know that one of the seeds is oppression of dark skinned Americans. But we're still free to make of the garden what we will.

There's so much else I want to remember from this book. There's a boy named Aberdeen who's "sweet" on Ruth; a donkey that Ruth names "Thomas Boon" in a scene both light-hearted and heart-warming; the re-appearance of Curzon's old friend Ebenezer; an emotional reconciliation (174); and, of course, the answer to that question, Will they ever realize they love each other?

Laurie Halse Anderson. Ashes. Conclusion to The Seeds for America Trilogy. New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2016.

Friday, June 19, 2020

Before You Say Something You'll Regret...: Crucial Conversations

"Take a deep breath, Mr. Smoot. You're about to say something you'll regret."

I whipped around from the 7th grade girl who had made me so mad to face the boy who spoke those words behind my back. He was smiling, but very red in the face.

He continued, "Count to ten."

I did. Then I apologized to the class, laughed at my foolish reaction, thanked him, and did my best to meet the girl's needs. She only wanted to do well, and my instruction had not told her how.

That's my own contribution to the trove of similar anecdotes that show effective ways to handle conversation when it goes "crucial." These anecdotes often made me tear up, because nothing gets to me like forgiveness and reconciliation. There's the one about the wife who wants to feel appreciated more than desired (98); the wife who finds a nearby no-tell motel charged on her husband's account (149); and the mother whose daughter screams, "I finally get a boyfriend and you want to take him away from me" (170)

The authors slice these anecdotes up, filling the in-betweens with observations of what's going wrong, and what can make it go right. So each chapter is a kind of story, with a heartwarming denoument.

The basics are all present in my own anecdote. Look at yourself and others to see if a conversation has gone wrong. Apologize. Make it safe, expressing that you don't want the other to feel badly, and you do share a common goal (and if you don't agree on a specific goal, make the goal more general). Find out,Why would a rational, decent human being do what they're doing? I've always known, true authority is based on mutual respect.

Here are a few gems from the book:

- Sarcasm is a form of silence (75)

- Respect is like air: You don't notice it, but when it's gone, it's all people think about (79-80)

- When a conversation turns crucial, "step out of the content" to examine why there's "silence" or "violence," sure signs that someone doesn't feel safe (92 and before)

Some of the book's lessons are good for teaching my students about persuasive rhetoric. There's a list of ways to win an argument by hurting everyone and shutting down true dialogue:

- Stack the deck with our supporting facts

- Exaggerate

- Use inflammatory terms

- Appeal to authority

- Attack the opponent

- Make hasty generalizations

- Attack a straw man

One of the many stories contributed by readers concerns using the principles in this book to compose a speech for an international audience filled with defensive delegates (222). For teaching persuasive writing, these are understandable notions: make the other side feel "safe" and mirror the other side's stories.

The authors' use of the word "story" is helpful. It's better for teaching writing than the dry word "thesis." Facts don't have power to make us emotional, but the stories we make from them do. If you're feeling strongly, then examine your story. Often, there's more than one story to explain the facts (115).

Also, vocabulary matters. "Angry" doesn't give you enough information; "surprised" and "embarrassed" give you some things you can address (114).

Some of the strongest stories and lessons follow the index. In an afterword, the authors tell what they've learned in a decade of teaching this book. These are strong:

- It's not only when it matters most that we do our worst. The author blew up at a minor $3 charge (224).

- Ready to launch a tirade at his 15 year old son, the father took a moment to examine the boy's story. When his own body visibly relaxed, the boy transformed, "no longer a monster -- he was a vulnerable, beautiful, precious boy" (226).

- You can't make someone else have dialogue with you. But weeks of the father's approaching the withdrawn, sarcastic daughter, "softened" her to the point that she felt safe to tell him her story (230).

One author tells us that some readers who thank him for the way the book has helped in their lives also admit that they've not done much more than skim the book. He says that's okay. We all have good ideas of what best behavior looks like, and just the reminder that a conversation has turned crucial is enough (228).

When that happens, take a deep breath. Count to ten. And start over.

Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When the Stakes are High by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler. Second Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2012.

Wednesday, June 17, 2020

"Forge": Friendship and Fire

[Image: Laurie Halse Anderson. Forge. New York: Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2010.]The jokes are a guy thing, natural to Anderson's narrator Curzon. In Chains, the intense story of Isabel, a girl enslaved, Curzon was comic relief, with his ridiculous floppy red hat, an earring, military garb too big, and a mouth on him. Even at the end of that story, sick and starving in a military prison, he's making jokes. Now he's "almost 16," meaning 11 months short of his birthday, enrolled in the Continental Army, longing to reunite with Isabel.

Friendship leavens Curzon's suffering from the elements, privations, and hostility from a few of the other teenaged boys in his company. Foremost among his allies is Ebenezer "Eben" Woodruff, the young soldier that Curzon saves early in the novel. Eben's gratitude is as boundless as his chatter, expressed often with arm-numbing punches to Curzon's shoulder.

A gulf opens between the two friends in a passage that anticipates how the "seeds of America" in 1777 will grow through Civil War to Civil Rights to those today who pit "law and order" against "systemic racism." When Eben argues that runaway slaves break the law, Curzon counters, "Bad laws deserve to be broken," just as the King's decrees are being rebuffed by the colonies. Eben asserts that "running away from their rightful master is not the same as America wanting to be free of England." Curzon falls silent a moment.

I almost told him then; told him that I and my parents and my grandparents had all been born into bondage, that my great-grandparents had been kidnapped from their homes and forced into slavery while his great-grandparents decided which crops to plant and what to name their new cow. (66)

If they'd had the phrase "white privilege," Eben still wouldn't understand. When Eben counters that bondage is "God's will," Curzon walks away: "You're not my friend." The ugly and painful chapters that follow make the friendship, when it returns, all the more deep and sweet.

To fit the arc of Curzon's story to a day-by-day account of events in 1777-1778, Anderson paces her chapters to make the personal coincide with the historical so that jaw-dropping surprises don't feel random. Instead, for example, we think, "It makes sense they would be there!" Anderson shows off in a playful way, meting out highpoints to fall on significant dates. There's peace-making and good will on Christmas, very bad luck on Friday the 13th, something having to do with the heart -- no spoilers, here -- on February 14th, and, for May 1st, more than one reason to think that our narrator has Maypoles on his mind. The way Anderson plays with her material to hit these marks adds another pleasure to the novel.

Anderson plays with the title, too. When my seventh graders read Chains, there's always a bubbling up of energy as the kids realize how many ways the title appears in the text, relating to story and themes. That game continues, as Chains are made at a Forge. Much of the novel takes place at Valley Forge. Curzon, who once worked for a blacksmith, makes himself a black "Smith" when he enlists with an alias. The hardships of military life are a "forge," says a fellow soldier, to be "a test of our mettle" (121). Lead antagonist James Bellingham has forged a metal collar for his slave. By training during the spring, ragtag soldiers are "forged" into an army. Then, forged notes are part of Curzon's escape plans.

Of course, there are no forges, no chains, without fire, and a singular passage about fire and chains confirms the strength of the fire that burns in Curzon. He tells of hearing a story from Benny, the runt of the company whom Curzon admires for courage. It's little Benny who shames a bully to tears for shirking (140). Curzon bites his tongue to keep from laughing when Benny, trying to fit in with the big boys, cusses "like a granny," Oh, foul, poxy Devil! (95). Curzon, who cannot read, listens intently when Benny tells stories to his mates.

The story of the Titan Prometheus, chained to a rock for sharing fire with the needy, comes to Curzon's mind at a moment of intense hopelessness. Bellingham has outmaneuvered him: since Curzon is inured to pain, Bellingham threatens to punish Isabel for any misstep by Curzon. Moments later, Curzon stares into a fireplace and recalls the story, though not the name, of a "fellow ... chained to a rock where an eagle ate out his liver, which grew back every night, and so on through eternity." Curzon reflects,

When Benny finished his story... I did not know what I would have done if somebody shackled me to a mountain and sent an eagle to eat my insides, day after day after day.

Now I knew. I would fight the eagle and the chains and that mountain as long as I had breath. (199)

I was overcome by an unsettling sensation, as if some giant had picked up the whole of the earth and tilted it. She'd been hurt, scarred on the inside of her spirit, and I did not know how to help her. (189)

Take your hand off her, you foul whoreson.

"Of course, sir," I said. (207)

Not Isabel. The reverse side of her pigheaded stubbornness was unshakable courage that was worthy of a general.

"If our luck does not turn for the good on its own," she said, "we'll make it turn." (270)

Wednesday, June 10, 2020

Around the World on a Bike

Tomorrow, I start going the other direction. This is something Dad did, running 25,000 miles over a period of years. Happy to continue the tradition.

PS - I've decided to do something different. I'm logging my miles on a virtual tour of the USA, stopping to take virtual selfies at places I've lived or loved. See my page Cycling America, Virtually.

Friday, June 05, 2020

Mary Karr's "Sinners Welcome": Discomfort and Joy

If you've never been a kid, and choose to raise one, knowIn this poem, she calls her alcoholism a "sarcophagus" that "boxed" her in before his baby cries "ripped through the swaths of ether I hid in." Nearly twenty years pass in a line as "he grinned up and eventually down / to me from his towering height" and his breathing, his life, freed her from her "ribcage," her self.

he'll wind up raising you. From whatever small drop

of care you start out with, he'll have to grow an ocean

and you a boat on which to sail from yourself

forever, else you'll both drown. ("Son's Room" 54)

But in the muted womb-world with its glutinous liquidThe Trinity pervades her retelling of the Crucifixion. She spares no gruesome detail as she describes the nails, the sagging rib cage, the suffocation, wondering "if some less / than loving watcher / watches us." Then "under massed thunderheads" the man on the cross feels his soul "leak away, then surge" as "wind / sucks him into the light stream" and "he's snatched back, held close" (52). In Karr's imagination, the Resurrection is wholly physical, the word "Spirit" translated literally as "breath": "In the corpse's core," she writes, "the stone fist of his heart / began to bang on the stiff chest's door / and breath spilled back into that battered shape." She rounds out the Trinity with the assurance to us, "Now it's your limbs he longs to flow into... as warm water / shatters at birth...."

the child knew nothing

of its own fire....

He came out a sticky grub, flailing

the load of his own limbs...

("Descending Theology: The Nativity" 9)

Wednesday, June 03, 2020

Firebombing and Force: What's "Strong?"

To impose discipline once and for all, I did the worst things I've ever done -- hitting the dog, losing my temper at a student. Even when you get the satisfaction of feeling your power over others, their fear of you builds a reservoir of rage and resentment. Whatever you hoped for -- a loving pet, students eager to learn from you, a community of mutual trust and respect -- you've doomed it. Next time, the demonstrations of power on both sides will be even more destructive.

Our President called governors "weak" and threatened to override them with "strength." He said, "You're dominating or ... you're a jerk." In response, commentator George F. Will called the President a "weak person’s idea of a strong person, [a] chest-pounding advertisement of his own gnawing insecurities" (June 1).

If our President were to open the Bible he brandished the other night, he might see numerous times when his kind of "strength" failed God Himself, when awesome force failed to make His people do right once and for all. God tried expulsion from Eden, a world-wide flood, fire from heaven, and opening the earth to swallow the rebels. Psalm 78 alone gives 72 verses' worth of God's forceful actions that didn't have lasting effect. It works the other way, too: when emperors exerted force to make the Jews bow down to them once and for all, the Jews refuse, dance in the furnace, sleep beside lions, and light the menorah.

Jesus lived under oppression from his birth to his death. The massacre of babies at his birth was to protect Herod's claim to the throne; the crucifixion was to stop the Jesus movement once and for all. Theologian Howard Thurman, mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr., outlines how other Jews resisted Roman oppression. Some, such as Herod and the much-reviled tax collectors, cooperated with the Romans; the Pharisees enforced Jewish identity and separation from the Romans; the Zealots advocated violent insurrection. Among the apostles of Jesus were some from each group. Thurman shows how each of their ways came with an intolerable cost, from loss of self-respect to violent retribution.

Jesus offered another kind of strength: radical respect for the other, love on a societal scale. Jesus stood up, told the truth to the religious and political authorities, but did not shun Nicodemus the Pharisee nor the Roman centurion whose daughter was ill. At the start of his ministry, Jesus refused Satan's temptation to bring about the kingdom of God by power. Jesus exalted the poor and weak and welcomed outcasts and foreigners. Asked would he forgive anyone as many as seven times, he replied, "Seventy times seven." When Peter defended him, Jesus commanded Peter to put the sword away. Hanging from the cross, he was mocked for having power to save others but not himself.

In our present context, what would Jesus' kind of strength look like? Our creator "became flesh and dwelt among us," says John's Gospel. I imagined what would happen if police officers facing a crowd were to take off their armor, put down their weapons, and join the demonstration. To my surprise, I learned that's what happened in Flint, Michigan and other places around the country. [See collage]

So, once again, the second time in just a couple of weeks, a camera has broadcast the killing of an unarmed black man by white men confident the state will back any white man who claims to have felt threatened by a black man. Once again, while politicians express dismay at the most recent killing, some (such as the President's spokesman Jake Tapper) deny that this kind of event happens routinely. Once again, both sides face off.

Once and for all, can we agree that there's a better way?

- Blogposts of related interest:

- Racism is about fear before it's about hate (07/2016)

- Howard Thurman's Jesus and the Disinherited: Real Prophecy. (12/2015)

- A year before George Will called the President a "weak person's idea of a strong person," I wrote how this president is a 13-year-old boy's idea of a great leader: America's First Teen President and Other Adolescent Power Fantasies (07/2019).

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Theology for Breakfast: Keepsakes & Armor

Richelle Thompson. Daily reflections on scripture in Forward Day by Day, May 2020. Cincinnati: Forward Movement.

"For my days drift away like smoke," sighs the psalmist (102.3) some 2700 years before shelter-in-place orders. When Richelle Thompson was composing her meditations for Forward Day by Day, COVID-19 was not yet a thing. But her bite-sized essays have been a consistent pleasure to mark the passing of this month.

When her days are like smoke, and she lies awake in bed like that sparrow lonely on a housetop (102.7), she gives thanks that Psalms so often express exactly what she feels. She challenges us, when the days drift by, to pray to be as fully present in each moment as God is to us.

For Richelle Thompson, gratitude is equipment like the "helmet of salvation and the sword of the spirit" (Eph. 6.17) to prepare us like superheroes "to face, if not evil, then the challenges of the day." She suggests other protections:

- Encouraging passages of scripture that, like God, stay with you wherever you go (Joshua 1.9); Thompson compares these to cherished tokens on her desk from other times in her life that remind her of what she's come through and what she wants to do;

- Lists of details like all those instructions for the ark in Exodus 25, which remind Thompson of instructions from IKEA. She wonders if Exodus is telling us that small details matter? She challenges us to keep a list this week of small acts of faithful generosity;

- Lists of things for which you are grateful;

- The names of laypersons in your faith community you can lift up for doing amazing things in your midst.

Besides lists, storytelling can make an even greater difference in our lives. Thompson observes that Jesus speaks in parables (Matthew 13.10) so that his teachings come as "lived experiences" instead of "rote recitations." She shares a couple of memorable examples from her own family that will stick with me, I hope. When the psalmist prays, "let me not be disappointed" (119.116), Thompson tells us of a beach house intended to be a reunion spot for generations of her family, until divorce wrecked that dream. The good news is, new traditions grew up around the place, and the disappointment is redeemed. Thompson relates the parable of seeds to parenting as a great act of faith. She recounts how her two teenage children in separate incidents used their own money to buy shoes -- one pair for a barefoot child at an after-school care center, another for a classmate who'd worn the same sneakers for three years. The teens had been especially difficult that week, but these acts of generosity came as reassurance that the seeds planted early in their lives were bearing fruit.

A couple of her stories riff on Biblical lines about gates. "I am the gate," Jesus says (John 10.9), but Thompson tells of her daughter's gate-phobic horse. Her daughter's competitors set aside their rivalry to lure and nudge the horse through the gate into the arena. Do we need to be nudges, or nudged? The narrow gate (Matthew 7.14) reminds her of a retreat called "Narrowgate" on a cattle ranch where a trench overlaid with metal pipes is enough to keep cattle from crossing through a wide gate into the parking lot. The cattle, having poor depth perception, are frightened off by shadows in the trough. We, too, may draw back from wide gates in our lives from unfounded fear.

Sometimes Thompson finds a positive spin on scriptures that have bothered her. She wonders of Paul's admonition wives obey your husbands (Col. 3.18) might not have been "a blunt tool" to suppress women but Paul's "lever" to lift women up into the consciousness of his highly patriarchal listeners? Bothered by political strife, she tries to pray for enemies and trust God (Mt 5.44). She wonders why the passages that compare God to a refining fire always use silver for the image, instead of gold or copper (Ps 66.9). She reads that silver is more resistant to corrosion, and more reflective: Could it be that those refined by God thereby become more persevering and reflective of His love?

At the end of each reading is a one-line challenge with the motto, Going Forward, and Thompson's seem especially promising. She challenges us to think on a scripture that bothers us, to find a new way to hear it. She challenges us to take the commandment literally to love our neighbors -- and to invite actual neighbors in. Responding to Psalm 40.13-14, she urges us to let ourselves admit "God, I am overwhelmed." Relating the stone that the builders rejected to young gadflies Greta Thunberg and Malala Yousafzai, she challenges us to think of an unlikely person who speaks an important truth that we may need to remember. She asks, "How could you surprise someone with a gift of grace today?" Wondering about the phrase "stiff-necked people" in Ex. 33.36, which appears more than 40 other times in scripture, always as a quality that God detests, Thompson challenges us to discern the difference between determination and stubborness.

A new month brings a new author in Forward. I'm looking forward.

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Where Prayer Meets Poetry: The Collect

Karr discovered that prayer, even the kneeling part, changes the pray-er. "Like poetry," she writes,"prayer often begins in torment, until the intensity of language forges a shape worthy of both labels: 'true' and 'beautiful'" (74). (Mary Karr. "Facing Altars: Poetry and Prayer." Essay in Sinners Welcome. New York: Harper Perennial, 2006.)

Forming a prayer that comes close to being a poem is something that my adult class at St. James Episcopal Church does each week. We follow the curriculum "Education for Ministry" (EfM) devised by the School of Theology at the University of the South, Sewanee. Each week we apply our readings from Scripture, history, and theology to a story or artifact brought to us by someone in the class. We end by collaborating on a collect, intended to "collect" all our thoughts into one unified prayer, often one sentence. We wrestle with the problem of finding the words that are both true to what has emerged from our discussions, and beautiful.

Here's a collect that we composed when our student Erica brought us Mary Karr's poem "Etchings in a Time of Plague," which could've been our time, early in America's COVID-19 emergency. But Karr published the poem in 1993, the height of the AIDS epidemic. The title refers to a Medieval etching of a cart carrying plague victims, one white hand sticking out of the carnage like a flower. In the poem, a subway rider lifts her eyes "from the valley" of the art book in her lap to see a "frail" young man. In her mind, he becomes "everyone you've ever loved" and, at their stop, she thinks, "Offer him your hand. Help him climb the stair." After our discussion, we wrote this:

Collect for a Call to Action

Eternal God, when Your hand set Ezekiel in a desolate valley to proclaim hope, dry bones rose to new life: may we, like Ezekiel, look up from our personal valleys to act as Your hand and voice to those who need comfort. Amen.

For tying together all the strands of an occasion, this collect might deserve a prize. The "valley" line of the poem brought to mind Ezekiel in a valley of dry bones, fresh from Sunday's scripture reading. Before we'd read the poem, we'd discussed an essay about "vocation," God's "call" to us to act. Valley, plague, a skeletal body, a hand, and a call to action: we packed it all in one sentence.

Derek Olsen outlines the form of the collect in his guide to the Book of Common Prayer Inwardly Digest. A collect begins with an invocation calling God by a trait appropriate to the occasion. (For ours, perhaps "Life-giving God" would be more fitting.) Olsen calls the next part "the relative clause / acknowledgement," a reminder of a characteristic or action of God that fits the occasion. Here, it's Ezekiel's famous prophecy. Then there's "the petition," a request of God, followed by the "statement of purpose / result." At the end is a "doxology," here shortened to "amen."

More than the form, which can vary, it's unity that distinguishes a collect. For contrast, Olsen cites the prayer attributed to St. Francis, Where there is hatred, let us sow love; where there is injury, pardon.... Karr calls it both prayer and poem, for her a gateway into faith. Yet Francis's prayer, being a list of several balanced petitions, lacks the concentrated focus of a collect.

Collect for a Time of Upheaval

Almighty and merciful God, when You through Jonah warned Nineveh that the great city would fall to nothing in just forty days, the citizens repented, fasted, and averted catastrophe: May we, shocked by sudden awareness of our precarious condition, see with new clarity the beauty and value in routines we have taken for granted, and abjure the fruitless anxieties that have distracted us from You. Amen

For me, being an English teacher, part of the fun is to pack all of the discussion into a single forward-moving sentence. The collect marches smoothly in iambic steps through the story of Nineveh until the accents reverse after the dash "may WE -- SHOCKED by SUDden a-WAREness," appropriately stopping us in our tracks. The rhythm is one reason why Olsen advises that a single trained reader deliver the collects. They are written to sound beautiful, "charming the ear by putting similar sounds close to one another" and flowing in "rhythms and cadences" that crowds' voices would muddy (131).

One collect was all mine, as our discussion ran long. There's only so much Zoom my eyes can take! Our student Pete had shared a photo of "Holy Water" in a cheap plastic bottle with a stamp attesting to its coming from a spring in Conyers, GA, blessed by Jesus Christ "personally" in 1969. We scoffed at the very idea of holy water as a mass-produced commodity, but then remembered that we kneel reverently to sip Mass-produced consecrated wine: to people outside our tradition, what's the difference? For them, our own rites -- hand-waving, water-sprinkling, bowing, petitions -- are ridiculous.I'm personally invested in this one. A glance at my Episcopal page reveals that the point where magic meets mystery, where fantasy meets myth, has always been the fulcrum of my faith -- my whole inner life. The form of the collect helped me to bring all of our discussion together to make a statement that, for me, resolves the issues:

Collect for Consecration

Almighty Father and Creator, by the power of Your Holy Spirit, You exalted humble Mary to be vessel of Your birth, You make Yourself present in the ordinary bread at Your altar, and You promise that a spring of living water wells up in each of us to eternal life: now consecrate our senses that we may perceive in our neighbors, our selves, and in all Your creation, Your power to make instruments of Your grace. Amen.

Examples of God's working through scoffed-at vessels pile up against that colon like a stream behind a dam; after the colon we get a release of energy at the recognition of God's power to consecrate us.

Discussing a story of a guest who chooses not to question signs of criminality that he finds in his host's library, we collected examples of how Jesus does ask crucial questions, respecting the unique concerns of each individual he questions. At least for those who know the gospel stories, this collect is a compact manual for how to have difficult discussions:

Collect for Empathy

Lord, creator and sustainer: you asked questions that probed the hearts of the people you met, Will you sell your possessions and follow me? Can you surrender your authority to be newborn? Do you wish to be healed? Train our imaginations so to empathize with those we meet, that we, too, may ask the questions that lead to safety, growth, and health. Amen.

Olsen makes the poetry connection explicit. "A good collect should be like a haiku," he writes...

...in that it gives a unified experience, communicating a single, self-contained thought. Furthermore, this thought may be allusive, using loaded language to point outside of itself to references that a culturally literate interpreter should pick up. Finally, a good collect should leave us with a feeling, an intention, or a resolve to enact that for which we have just prayed (138).

From experience, I'd only add that the feeling you get from reading a good collect is heightened when you've struggled with friends to write one. As Mary Karr's friend might say, you're not writing to change God's mind; you're writing to change your own.

- Blogposts of related interest:

- See our EfM class blog.

- About Derek Olsen's book, see more at my blogpost "The Power of Liturgy: I've Heard it All Before" (01/2017)

- "Mary Karr's Sinners Welcome: Discomfort and Joy" (06/2020).

Monday, May 25, 2020

For Memorial Day: "Mostly Ghosts" by Bee Donley

Bee remembers, "We, the wives and girlfriends, listened and smiled, / ...Loved you extravagantly with our eyes and hands / Knowing we were the unseen." The men's wartime experiences, more compelling than peacetime, has made ghosts of the women who loved them.

[PHOTO: Bee Donley in her late 80s, looking just as I remember her from her late 50s. Photo from an interview with the Jackson Clarion-Ledger]Among the men she addresses as "you" is one she married, whose grave she visits 46 years after his "untimely" death to discover that the date is wrong. "I wonder," she asks, "if the ghost of that once smiling flier knows how wrong" ("Burial Ground" 6). In these few lines, Donley implies that the ghosts of war never let go of him, and we can guess at the young father's suicide -- something I heard about, never from Bee.

Bee Donley remembers another ghost between lines of the liturgy for "Memorial Day: Morning Prayer" (9). In her telling, a young pilot named Peter Joseph O'Toole becomes vivid to us, though she cannot remember his appearance, or whether he kissed her. "Yet the morning heat walking beneath the live oaks / to the campus P.O. for his daily letters seems real," and his imploring her, I know you probably won't answer, but I've never known a Southern girl before; it would mean a lot to hear from you. But he was killed in his first mission, "And now over sixty years later I pray for this boy I remember only by his name." So do we.

A Marine pilot, her brother, is another ghost made vivid in life and poignant in death through a multi-layered poem, "Reading Wordsworth and Remembering." Beginning with an epigraph from Wordsworth about "the best portion of a good man's life" being "nameless, unremembered acts / of kindness and of love," the poem tells the anecdote of her younger brother's building box kites to delight Bee's five-year-old daughter, his niece. One tangles in a tree; the other falls in a sharp downdraft. Bee shifts to the image of the young pilot's plane suddenly plunged into the sea by downdraft, leaving her "searching cloudless skies for," in one of Wordsworth's most famous lines, "trails of glory."

Other poems in the collection conjure the life of a Southern daughter of a Mississippi landowner. What stands out the most is something she says she learned from her father: "He taught me not to cry... I do hold my shoulders up."

Even enduring treatment for cancer, Bee Donley sat up in bed with plumped pillows and unruffled sheets to offer her apprehensive visitors wine, her hair perfect, collar raised, robe falling about her in a semi-circle, slippered feet tucked to one side -- as if she were posing for a magazine spread on boudoir fashion. Bee was my oldest colleague at St. Andrew's Episcopal School in Mississippi, so poised on her high heels, so tireless in her many roles at the school that, seeing how unbowed she was by cancer, I figured she was immortal.

So to see her obituary pop up during a Google search came as something of a surprise, though nearly 40 years passed between then and her death in January 2018. But I was delighted to learn that she published poetry in her 90s. Mostly Ghosts is an apt title for her first collection, because she lives on in the lines.

Friday, May 08, 2020

Dementia Diary: What Virus?

Good news: "Really? What virus?"

Laura Robinson of Visiting Angels, Mom's companion for several years, now, took this photo from inside the dining hall when I came for a visit outside the window. Mom and I spoke through Laura's phone.

Tuesday, May 05, 2020

Asynchronicity for Deep Dive Education in Middle School

The whole time we were meeting, I was nominally "in class," but free to talk because my students had "asynchronous" work to do, editing their portfolios and reading a chapter. They had nearly an hour to work on their own before they would join me for a short synchronous videoconference, part spoken discussion in "break out" rooms, and part written comments on "chat." Students who missed it all did it all by email later in the week.

Later, I saw that the asynchronous techniques of distance learning could be the key to creating a "deep dive" experience for students motivated enough to want it. The answers to all of our Head's practical questions, printed below in italics, fell in to place:

- What are the pre-requisites? What is the interview process? What restrictions are there on the program? Participating fully in regular synchronous classes during the first quarter, students who self-identify as interested in the program are evaluated for traits of curiosity, near-mastery of the skills exercised during class, and willpower to work independently.

- What personnel are involved? In our school, our classes rotate in a cycle of seven days, and each class meets six times. Students who qualify for this program come to half of classes in their field for three days, keeping up with reading and discussion, other days reporting to the media center or a middle school classroom set aside for asynchronous study. During the second quarter, they spend that time researching broadly in their field. They will need a study advisor -- not necessarily the same as their classroom teacher -- and, being middle schoolers, some adult in the room. By the end of the second quarter, they and their study advisor will have mapped out a course of study: sources to read, or people to meet, or data to collect.

- How does this align with extant curriculum, especially with classes in the higher grades? Throughout the third quarter, and some time beyond, the students will do the deep work of following the map they made in the second quarter, collecting data, quotes, impressions, pictures -- whatever -- going deeply into a tangent to the same subject that their classmates are studying. They're not "getting ahead," but going deep.

- In the fourth quarter, they collect what they've learned into a form that can be presented to classmates, teachers, parents. Tools that we're using for distance learning could be useful, here. Over time, the school will have accumulated a library of videos and virtual books for use in the classroom.

While the terminology of "asynchronous" learning comes out of the world of on-line experiences that may or may not happen "in real time," technology only facilitates the kind of educational experience that, in my own life, has been most valuable. Looking back through my own secondary education, I realize that all of my ah-ha moments happened because the teacher got out of the way. While we read Faulkner with Mr. Scott, he had us choose another Faulkner novel of our own choice, to write on a topic of our own devising. Mr. Boggs sent me off to put together a program of songs by Sondheim. (Read my tribute, 11/2015). At Duke, Professor Holley assigned a research paper on the first day of class that had to be about something on Duke's campus that had never been researched before. My first draft, due in December was 20 pages long; my second, in May, was 40 with 40 more pages of notes from letters, interviews, and yellowed original documents. (Read my tribute to Dr. Holley 09/2013) A graduate professor at Millsaps College freed me to research solutions to the three greatest classroom challenges that I'd identified during my first three years of teaching, resulting in essays that still fuel what I do.

The program I've laid out, it hits me now, is pretty close to work I've done with all the students in my regular classes. My 8th graders came to two classes a week prepared to learn about American history through documents, but the other two classes, they circulated between conferencing with me and going to the library to work on research for a pair of related papers, one per semester.At St. Andrew's in Jackson, science teacher John Davis assisted fifth graders who had passions in an area to find grown-up experts in the field who became their "colleagues" on a project, and presented them with much fanfare to a live audience, child and adult both on stage. (I remember especially the one with the life-size papier mache whale.)

So, problems solved. I'm going to ride my bike this morning, so that I can meet my synchronous responsibilities in the afternoon.

Sunday, May 03, 2020

Stephen Sondheim, We're Still Here

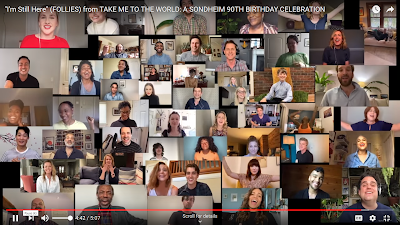

Take Me to the World, "I'm Still Here"

Unseen musicians provide note-perfect accompaniment, though a few performers sing unaccompanied: host Raoul Esparza does a portion of "Our Time," Mandy Patinkin sings "Lesson #8" out in a field on a cold day, and Bernadette Peters sang "No One is Alone" leaning up against the wall of her kitchen. Of all the birthday celebrations I've heard and seen, going back fifty years to one performed on the set of the original production of A Little Night Music, this one felt most intimate. I sang along and enjoyed every minute.

But I missed a few minutes at the end that made me cry when I saw them this morning. For a coda, dozens of performers do "I'm Still Here." Though it's a great song, it's not one you cry for, and the performers for once were a little punchy and not all on the beat. They sang the way I've done so many times in the car or the shower, just letting loose. That's where the tears came from: as the faces on screen proliferated, and the voices overlapped, I was made to feel part of the group, a community that includes the big name stars with those who were watching (and donating $400K dollars) -- the community of all those around the world who do know every word and who have sung "I'm Still Here" at the tops of their lungs when no one else was around.

Many of the stars from earlier celebrations are no longer with us. Others sound just as good now as when I first saw them decades ago, and many younger stars, unfamiliar to me, interpreted their songs beautifully. So I'm delighted to see that the community is still here, and still growing.

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Theology for Breakfast: "Faith in God is Never Abstract"

Some mornings, reading meditations on the day's scripture in Forward Day by Day, I mark ideas that I should reflect on again and again. The author of meditations for February 2020 was Mark Bozzuti-Jones, a priest at Trinity Church, NYC. Reviewing what I checked there, I see a theme emerge, coalescing in a single strong statement: "Faith in God is never abstract."

The context for Fr. Mark's statement is Psalm 89.2, "You have set Your faithfulness firmly in the heavens." Fr. Mark reminds us Episcopalians of the baptismal vows that we've renewed many times, actions that we are to take. I'm reminded that the ancients called the sky "firmament" because they envisioned it as a solid globe that revolved around us.

In other writings, Fr. Mark asks us to remember specific acts in the life of Jesus, and specific people in our own lives, that demonstrate grace.

When we remember the gracious acts of others we live more graciously. Recounting the gracious deeds of the Lord also encourages and instructs us about how to behave with grace. Nothing keeps our hearts more full of compassion and love than when we celebrate God's grace in our lives. (February 18).

Back in February, the daily readings were taking us through the stories of Abraham, reminding Fr. Mark that "the Bible is, at its heart, a love story" (February 7). He explains, "Abraham knows what he wants - a family, a place to belong - and finds these things in his relationship to God." God loves Abraham even when the old man errs. Fr. Mark continues,

Abraham and Sarah fall in love with God and each other, over and over. They teach their family to do the same, and in good time Isaac and Rebekah begin to write their own love story to God. Jacob and Leah and Rachel follow soon after, and the children of Israel are firmly established according to God's promises.

One meditation isn't by Fr. Mark, but from the dark days of World War II, Forward Day by Day of November 26, 1944, reprinted now as part of a celebration of Forward's 85th anniversary. That day, the meditator described looking out from windows along the spiral staircases of old watchtowers in Europe. Windows may look in the same direction at the same things, but the perspective is different as you advance up the stairs. In the same way, our perspective on passages in scripture and events in our own lives change with time.

Firmness, remembering specifics, following our vows: these are faith, not in abstract, but in deed.

Sunday, April 19, 2020

"Deep Gloom Enshrouds the Nations" - Isaiah 60.1-3

But these days, I've had to pause and shudder at the second verse:

For behold, darkness covers the land.

A deep gloom enshrouds the nations.

I'll admit that I, privileged to have a home, and work, and my health, have not felt so gloomy.

- My friend Jason has sent me a mask and daily updates of pandemic statistics that show some stabilization.

- My students have settled into a routine of writing for me and each other on a website discussion board and checking in for Zoom meetings that usually leave me feeling better for having seen and heard the kids.

- Brandy has loved having me home, and we take daily walks with our friend Susan.

- Caregivers at Arbor Terrace, plus Visiting Angels Laura and others, keep Mom company day and night. When Laura has helped me to communicate on WhatsApp, Mom hasn't been aware that she hasn't seen me in weeks.

- Though the county has closed down the Silver Comet Trail, I've been able to ride the 38 mile Stone Mountain loop once or twice a week as the weather has warmed.

But then Susan remarked off-handedly, "We're all grieving." She didn't have to explain; I immediately teared up. I'm grieving for the way life was, the things I thought I could count on, the plans I'd made -- all gone. The wait staff who knew us by sight, the launderer who has delivered me clothes, washed and pressed for each week of classes - that's all gone, and they're hurting, I know.

Then there's the news. Every day, I'm hearing of deaths nearby and far away, a world in distress; food banks depleted; doctors overwhelmed here and abroad. NPR and our local NPR station WABE give us personal interviews with people "on the front lines," kind and courageous, but sometimes desperate.

In the past three days, I've had glimpses of a coming Zombie apocalypse, fomented by purveyors of conspiracy theories calling for getting out your guns to fight social distancing. I threw away a respectable-looking faux newspaper, its contents entirely meant to whip up indignation at China and, by extension, people of Chinese descent.

I've got to believe that most of us still know that science is true regardless of who believes in it, and that most of us still carry around in our hearts Isaiah's words, part of our American DNA:

Nations will stream to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawning...Violence will no more be heard in your land, ruin or destruction within your borders.

You will call your walls, Salvation, and all your portals, Praise.

Jesus says to the disciples, "Peace be with you." Roger takes comfort from that, but adds that we are not to be recipients of peace only.

Peace that comes from faith, and care for others, are things we can offer, even at a social distance.

Sunday, April 12, 2020

'round Monk

Around Monk, there's an aura of reverence and mystery. To get inside that aura this past year, I read a Monk bio by Robin DG Kelley, ordered CDs, and played Monk's music regularly.

[Photo: The cover of Time makes Monk look intimidating; the text is worshipful. But in 1964, his Time's up. Rock is about to make jazz irrelevant.]

Robin DG Kelley subtitles his biography of Monk The Life and Times of an American Original, a title that raises the question, original what? Some wit in Wikipedia's article writes that Monk sounds like he's wearing work gloves when he plays the piano. Musical giant Leonard Bernstein, quoted by Kelley, says Monk's "a genius, of course," but a "crude" pianist.

On the other hand -- literally -- no less an authority than Duke Ellington, from the stage of the Rainbow Grill, announced, "Ladies and Gentlemen, the baddest left hand in the history of jazz just walked into the room, Mr. Thelonious Monk" (Kelley 430). Monk was gratified, but what about the right hand? The audience was left to wonder.

Monk in performance seems to slap at keys, with much collateral damage. (See him play "Epistrophy" with Charlie Rouse in 1963 on Youtube). For lovely recordings by Miles Davis on "'round Midnight" and Carmen McRae's wonderful tribute album, the bands filter out some of the rough edges that we hear in Monk's own playing.

But Monk could play right notes fast, had he chosen to do so. Kelley starts his biography with the story how Monk, on a dare, sight-reads a Rachmaninoff score at breakneck speed. Thus Kelley refutes both the accusations of Monk's detractors and the racial stereotypes of white admirers, to the effect that Monk was either uneducated and undisciplined or else instinctual and child-like.

That Monk could match the more popular flowing virtuosic style, but wouldn't, suggests that his interest in the music was in some other kind of beauty. Monk himself seems to have embraced that idea. His 1956 tune "Brilliant Corners" may be his way of reading the phrase "rough edges," and his title for a 1967 tune could be his motto, "Ugly Beauty."

Ellington's praise may sound like a left - handed compliment, but I think it's key. While Monk struggled for recognition through the rise of be - bop jazz, his promoters claimed that he was on the cutting edge of the movement, a visionary, ahead of his time. Not so his left hand technique, which was deeply rooted in gospel music -- he toured with an evangelist early in his career -- and in the "stride" piano of his mentors. Stride requires the left hand to leap octaves from the piano's lowest bass notes to the middle of the keyboard. That's a leap of faith unless you're an expert. The gradual movement up or down in the bass note gives the piece its structure; over that strong foundation, the right hand can indulge in whimsical dissonances for color and punctuation.

About those dissonances, Kelley writes,

Monk's chords were a product of years of training, experimentation, and a solid understanding of music theory. Monk knew it, which is why he became so annoyed when critics, musicians, even his admirers, described his chords as "wrong" or "weird."

Monk's pride and joy seems to be how he makes so much from so little. He repeats phrases to create larger patterns. That's close to the meaning of the word "epistrophy," the title he chose for an early hit that he never tired of recording. Most of Monk's song "Well, You Needn't" (a.k.a. "It's Over Now") consists of one rapid motif ("ya'NEEDn't") run up and down the scale.

His popular ballad "'round Midnight" fits the AABA profile of most American standards, but it, too, shows Monk's love of a strong bass and controlled melody. Over a slow stepwise fall of bass notes, the tune slithers around in tiny half-steps, then jumps wide intervals, suggesting sighs and outcries. Making the most of his material, Monk builds the song's B-section from a variation of the last phrase of the A-section.

I wonder if Monk resisted prettying up his compositions because he wanted the audience to see the craftsmanship -- the foundation, joints, and beams -- not a facade?

In the same way that he focused each song on just a small amount of material, Monk focused his career on a small repertoire. Monk mostly performed selections from his own narrow catalogue of around 70 tunes, played mostly at a slow speed.

He wanted spontaneity from his players, but he also commanded them to "stick to the melody." Many times, Kelley tells us how a player joining Monk on stage would feel it was a "trial by fire," even Monk's own son Toot. Monk wouldn't say what the next song would be, and wouldn't provide a written score.

Monk the man comes across as shy, but fierce in defending his music. He drove himself to ill health on club dates, tours, and concert hall performances to support wife Nellie, son Toot and daughter Boo Boo. When he suffered with what we now call bipolar disorder, his family supported him. For Monk, "family" extended to include fellow musicians Charlie Rouse, John Coltrane, Bud Powell, Sonny Rollins, and his patron the Baroness Pannonica.

The arc of Kelley's narrative is Monk's gradual building of an appreciative fan base until, just as he came into his own in the early 1960s, the folk-rock-pop industry sidelined jazz. Monk, who had been far out and avant-garde, was considered old-fashioned by 1970.

I end my year of Monk feeling comfortable with his music. It isn't pretty, it isn't smooth, but it's colorful, well-crafted, clever, whimsical, always distinctly Monk. I turn up the radio when I recognize a piece of his, and I smile.

Butterflies & Live Stream for Easter in Isolation

This strange year, when there could be no gathering in the church, blessings upon Child Education Director Nancy Eubanks for bringing out all those butterflies to line Polk Street, Church Street, and the 120 Loop.

The tug of the church this morning was so strong that Brandy and I joined our friend Susan in a walk from her home to the church. As we sidled past squirrels, other dogs, and one unflappable cat, Brandy appropriately barked to raise the dead.

[Photo by Susan, at the moment that Brandy noticed a dog in the distance.]

Home again, we tuned into Facebook where Fr. Daron and his family live streamed the Easter service from their living room. In his sermon, Fr. Daron said that Christ's Easter miracle doesn't erase suffering and death from our lives -- the resurrected Jesus still bears his wounds. The difference is, since God has been in the midst of suffering, sin, loneliness, anxiety, that we can be assured of light at the end of our tunnel.

But, especially in a time like this, we naturally wonder, where is that light? Fr. Daron reminded us of Martha, who believed in the resurrection at the last day, yet didn't feel comforted by that knowledge when her brother Lazarus died; the apostles, though they had the assurance of eternal life, ran away after the crucifixion. Can we be any different? Fr. Daron said, yes, because we have the Holy Spirit in our midst.

Thursday, April 09, 2020

Spivey Hall Scores with Team Sports

Just before the pandemic shut down both sports arenas and concert stages, recitals at Spivey Hall south of Atlanta already had me relating chamber music to team sports. Then a Weekend Edition sports reporter, mourning the cancellations of March Madness, compared sports to music: both bring us together with joy.

Though I get no joy from competition, I do treasure some sports memories of teamwork and personal prowess. One is the vivid memory of a high school football game in rural Mississippi, circa 1983. Junior Eric Bluntson, a little guy built like a fireplug, clutched the ball. While his teammates ran parallel to create a barrier on Eric's right, Eric weaved, dodged, deflected, and jumped over opponents eighty yards for a touchdown.

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center was like that. They performed at Spivey Hall February 23. Especially in the finale of the D major woodwind quintet by Anton Reicha, contemporary of Mozart, each player took a turn with a different musical phrase while the rest of the team followed a few beats away in parallel. Throughout the set of pieces, we sensed joy and camaraderie as players kept their eyes on each other to match tempos and to attain clean cut-offs. For pauses and humorously understated endings, Gyorgi Ligeti's piece Six Bagetelles demanded most team coordination and got the most laughs.

"The Voice of the Guitar" February 29 featured guitarist Milos Karadaglic with string players of 12 Ensemble. Milos sometimes played solo, sometimes shared the stage with the strings, and sometimes gave the stage to strings alone. He was the star player, the one telling us how he fell in love with the guitar's voice, and how his appreciation developed through exposure to pioneering virtuosos, how he learned the repertoire, and how a hand injury gave him impetus to listen and learn from composers in the realm of pop music - Paul Simon, Radiohead, and the Beatles. Throughout the program, verbally and with smiles and nods, he expressed confidence and pleasure in his teammates.

Sometimes, in sports, it's an individual's superhuman feat that transcends the score. I remember an overheated gym, an overheated crowd screaming, the home team down by two at the buzzer in double overtime, when home team sophomore Brad Teague hurled the ball the full length of the court: swish for three!

Angela Hewitt's piano recital March 8 certainly qualified as a superhuman feat of precision, control, sensitivity. She played Bach's Four Duets, Eighteen Little Preludes, the Fantasia and Fugue in A minor, and, after intermission, the French Overture in B Minor, followed at last by the Italian Concerto in F major.

Even at this solo recital, there was a team aspect to the music that her playing brought out to us. That left hand so often danced around the right hand, sometimes following in parallel, or, like the basketball player guarding the one with the ball, the left hand hopped this way and that to cover the right hand's surprising pivots.

For a lovely encore, she chose the serene "While Sheep Safely Graze."

Little did we suspect that would be the final concert of the season. But the pleasure of individual virtuosity and teamwork keeps on.

- Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

- Michael Brown, Piano

- Tara Helen O'Connor, flute

- Stephen Taylor, oboe

- Sebastian Manz, clarinet

- Peter Kolkay, bassoon

- Radovan Vlatkovic, horn

Spivey Hall

Sunday February 23, 2020, 3 pm

- Milos: The Voice of the Guitar

- Milos Karadaglic, classical guitar

with members of

12 Ensemble - Eloisa-Fleur Thom, violin

- Alesaandro Ruisi, violin

- Matthew Kettle, viola

- Max Ruisi, cello

- Toby Hughes, double bass

Spivey Hall

Saturday, February 29, 2020, 3 pm

Angela Hewitt, Piano

Spivey Hall

Sunday, March 8, 2020, 3 pm