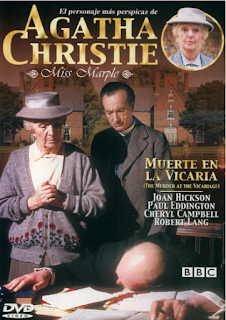

Agatha Christie was only 40 years into life and 10 years into writing when she created the elderly Miss Jane Marple for Murder in the Vicarage (1930). We can cut her some slack for some careless writing.

Agatha Christie was only 40 years into life and 10 years into writing when she created the elderly Miss Jane Marple for Murder in the Vicarage (1930). We can cut her some slack for some careless writing.Miss Marple herself scorns coincidence, allowing herself just one in her solution to the crime (250). Yet much of the novel turns on coincidences, such as a crucial misdialed phone call that just happens to go to Miss Marple. Her nephew Raymond is introduced late in the book just to bump into the one person that he would recognize at the small train station.

Christie gives us more details than I cared to enumerate fudging the time of the crime, which includes a forged note, a fast clock, and the coincidence of a late train.

Her prose is often first-draft quality. She relies on silly adverbs: Detective Slack tries "determinedly" to contradict his name, and our first-person narrator the Vicar tells us he looked "curiously." When he asks a question, isn't curiosity implied? Can he see his own facial expression? Here's a paragraph I'd have my seventh graders re-write:

Five clauses in a row begin "I" -- need I say, repetitiously? -- and, simply to pick up a letter, we slosh through colorless function words was,whether,when,there was,that this was the, and then wait for the vicar to hear, cross, see, presume, and take it out. This is padding.

I was just standing in the hall, wondering whether I would not even now go over and join them, when the doorbell rang. I crossed over to it. I saw there was a letter in the box, and presuming that this was the cause of the ring, I took it out. (252)

At her best, Christie can write a witty bit of dialogue. Told that an annoying witness fears she's next on the murderer's hit list, the detective remarks, "No such luck" (117). Miss Marple explains that "Intuition is like reading a word without having to spell it out" (92), a skill that comes with experience. Marple calls another character "morally colorblind" (281).

For a novel narrated by the town vicar, matters of faith are pretty superficial, along the lines of tut-tutting infidelity and telling how a woman gives him every opportunity to notice her pink-striped silk knickers (81). There's a remark about how the "high church" curate clashed with the church warden, "opposer of ritual in any form" (3). The town doctor tells the vicar how psychology blurs any line between right and wrong. "I believe the day will come when we shudder to think that we ever hanged criminals," the doctor says (121). It's out of character when the vicar finds himself extemporizing an emotional sermon on sin in his community that has consequences (240). (Read my blog post about "Christ in Christie")

So the author develops her plot without showing much concern for its characters or their world: both would come in some of her later works. This earlier work was at least a diversion, a welcome return at the end of a long day.

- Read more articles about Christie and others at my Crime Fiction page

- Personal thanks to Agatha Christie for an idea I've borrowed from Murder at the Vicarage for this year's murder mystery dinner theatre play at St. James' Episcopal, Marietta: What happens when three different suspects confess to the same murder?

No comments:

Post a Comment