This promotional tag printed in some DC comics in the early 1970s made me uneasy. At age eleven, I liked DC the way it was, uncrowded panels stepping us through the story from upper left to lower right, and its stories ending with bad guy in jail, hero in civilian clothes, life restored to normal until the next month's issue.

Jack Kirby cracked open my comic book world, as he had been doing since comics were new. Cartoonist Jules Feiffer wrote of Kirby's collaborations with Joe Simon in the 1940s, "Every panel was a population explosion -- casts of thousands: all fighting leaping, falling, crawling...Speed was the thing, rocking, uproarious speed" (Feiffer in Evanier, 49).

In the 1960s, with Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and others at DC's rival company, Kirby developed what came to be known as the "Marvel Universe," where characters' actions in one comic book had repercussions in another; a super-being such as the Hulk or Silver Surfer could be a hero in one context and a threat in another; a guy's personal problems didn't end when he put on his tights. Happy endings? Forget about it!

The Marvel model seemed chaotic and pretty depressing to me, so I remained wary when Kirby titles started to show up in the revolving comics rack at the drug store. But Kirby had created a meta-story for our world that had already involved my favorite DC characters: we learned that the corporation buying the Daily Planet was a front, making of Clark "Superman" Kent an unwitting employee of the evil lord in Kirby's inter-planetary cold war between New Genesis and Apokolips.

I surrendered to Kirby's vision, as did fantasy writer Neil Gaiman:

Kirby's Fourth World turned my head inside out. It was a space opera of gargantuan scale played out mostly on Earth with comics that featured (among other things) a gang of cosmic hippies, a super escape artist, and an entire head-turning pantheon of powerful New Gods. (Gaiman, introduction to Evanier, 11)

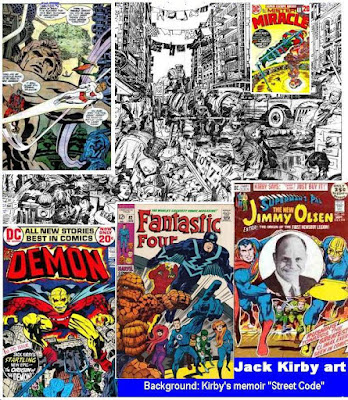

I learned to appreciate Kirby's damn-the-perspective, full-speed-ahead approach to drawing. His hobby of making photo collages may be a key to his style. Abstracted from their original context in photographs and pasted in a jumble, forms lose their function, and perspective vanishes; but odd juxtapositions draw the eye and challenge the imagination to make its own sense. See what I mean in the memorable spread from New Gods #1 pasted in the upper-left hand corner of my little collage of Kirby drawings created for this blog. Long curves, jagged lines, some kind of colossal statue, some disconnected machinery, some background silhouettes, together make no architectural sense, but all suggest a magnificent unearthly city. Biographer Mark Evanier comments about Kirby's collage-making,

The skill was not unrelated to the manner in which he created stories. Most of Jack's creations in comics were, at their core, a matter of taking unconnected concepts -- notions he'd gleaned from reading or movies or just sitting and musing about humanity -- and juxtaposing and/or melding them together in unlikely fusion. (171)

The black-and-white drawing in the background of my collage is part of "Street Code," Kirby's memoir of childhood, left unfinished in 1983 when his eyes made drawing nearly impossible. Mark Evanier's biography of Kirby, King of Comics, prints the whole thing in its rough penciled state, including distortions due to Kirby's eye trouble. But the two-page spread (see it online) is itself a collage of impressions recalled from the Lower East Side in the early 1920s, remarkable as anything else he ever drew. Kirby jumbles together glimpses of dozens of individuals all engaged in their own stories.

Kirby's own "spin on the American Dream," according to biographer Mark Evanier, was, "You make your boss rich and he'll take care of you." Evanier, who met Kirby around the time that the artist quit Marvel to move to DC, observes, "All Jack's life he believed in that, no matter how many times the bosses got rich and he didn't" (37). Exhibit A is "The Incredible Hulk Poster" that came to symbolize for Kirby what he saw as Marvel's lack of consideration for Kirby's work. "He'd created something that was potentially profitable... but he hadn't received a cent and someone else's name was signed to work that was essentially his" (159).

Evanier's chapters cover Kirby's hard-knock childhood, apprenticeship copying others' art in basement "factories," creating "Captain America" with Joe Simon, quitting when Kirby and Simon saw no reward for their work, war in France, fruitless attempts to find an audience in the 1950s, reinventing the super-hero genre in the 60s, and the DC days. Kirby was a prolific worker, but restless, always trying to climb the next rung of a ladder. No matter how successful his comics were, Kirby was "chained to the [drawing] board," haunted by the recurring nightmare that he might find himself again on the streets, unable to support his wife Roz and their children. Roz sometimes feared that "Jack would literally work himself to death" (138). But his eyes and hand gave out before his heart. Five years after his death in 1994, DC responded to reader interest with a reprinting of Kirby's "fourth world" saga that sold well.

Kirby's story might be sad, but Evanier leavens the biography with tributes to Kirby from movie makers, writers, and artists attesting to his lasting influence. Evanier inserts short essays about the craft, such as the one about collages (171), and others about the effect on Kirby's work of the self-censoring "comics code"(88), and about Kirby's collaborator Mike Royer on the art of inking pencil drawings (179). As one would hope, there's page after page of Kirby's art, bursting with energy and humor.

Evanier, Mark. Kirby: King of Comics. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 2008.

Novelist Michael Chabon lists Jack Kirby as his inspiration "above all" for his wonderful novel, set among pioneering comic book creators, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay. Read the second of my two reflections on that novel here.

No comments:

Post a Comment